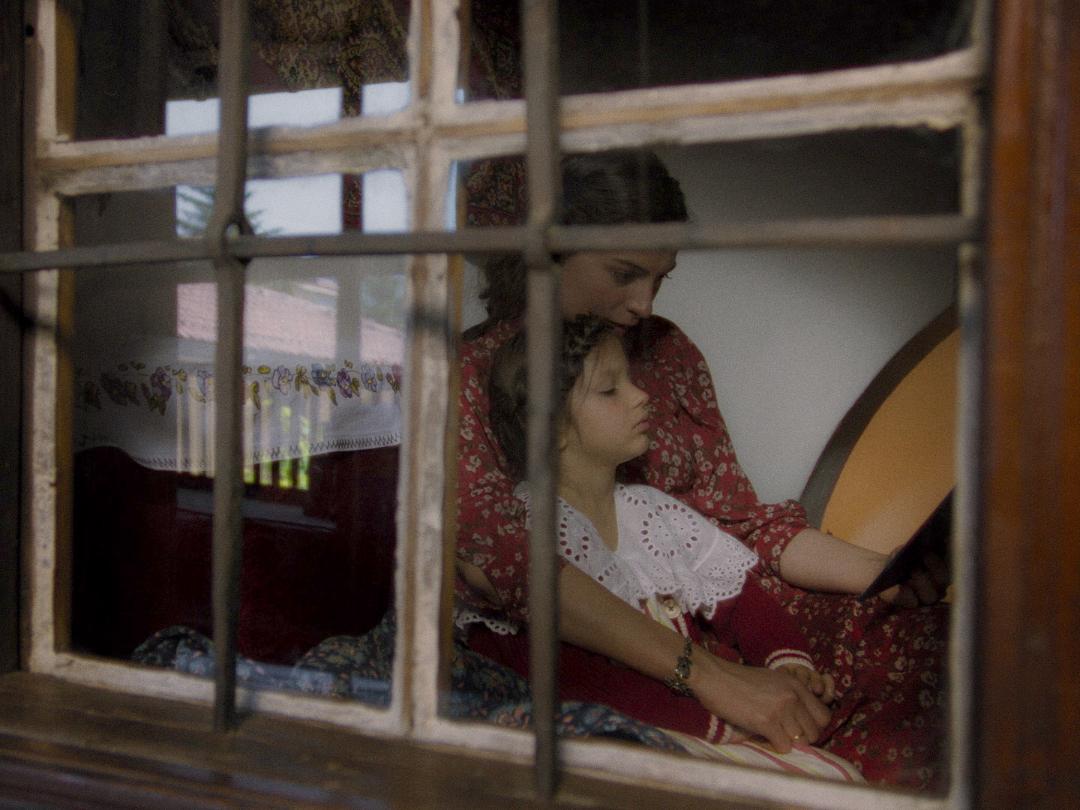

Film-maker Sabina Vajraca explores cross-generation bonds in her new short SEVAP/MITZVAH.

Film And TV Now spoke with the director about the short.

The story reflects two generations affected by war. What was the start-off point for the short?

Back in the spring of 2021, Gaza was in the news again, together with the same old rhetoric of Muslims and Jews being mortal enemies for as long as anyone can remember.

I recalled similar words flooding the U.S. media back in 1994, when we immigrated here as war refugees, saying that Bosnian Muslims and Serbs had hated one another for thousands of years and that the war we fled was inevitable.

That was not true at all (so many of our friends, neighbours, and family members were Bosnian Serbs and there was never any hatred there) so it made me wonder how much of the Jews-Muslim hatred propagated in that same media now was fabricated for the sake of sensationalism as well.

I knew about Muslims saving Jews in WWII Bosnia, for example, so I started looking into those stories, wanting to use it as a starting point from which to tell a different narrative. Once I came across the photo of Zejneba and Rifka and read their story, I knew I had my winner.

Around the same time, I learned of the Claims Conference film grant, and I applied to it with this script. When I won it some 6 months later, I was ecstatic, and knew that I’m not crazy – this story is important to be told and now I had the money to do it. (Thank you, Claims Conference!)

How much research did you do when writing the script?

I read everything I could find in the story, both in English and Bosnian. There wasn’t as much out there as I wished there would be, but enough to give me the starting point from which to weave my script.

Since then, while filming the short, I learned a lot more about Zejneba and connected with her son and granddaughter, who gave me a treasure trove of information, which I aim to incorporate into a feature version of the film.

Tell us about your cast.

I firmly believe that 80% (at least!) of the director’s job is casting, and I’m very involved in that part of the process.

It is also super important to me to establish a trusting relationship with my principal actors well before we get on set, and I make it a point we get plenty of personal bonding time over coffees and lunches well in advance of the shoot, especially when we don’t know each other already, as was the case here.

The only actor I knew from before was Frano Maskovic (Josef Kabiljo), who has been a close friend for many years, and whom I’ve been wanting to work with as long as I’ve known him.

I met Adnan Haskovic (Mustafa Hardaga) through a mutual friend a year before. All the other actors were discoveries for me. My friend Vanja Nikolic helped organize self-tape auditions while I was still in the U.S., through which I found Zejneba (Helena Vukovic), Rifka (Magdalena Zivaljic-Tadic), and Ivica (Rijad Gvozden), and the rest I cast once I was in Bosnia.

I’m incredibly grateful to all of them for jumping into this project wholeheartedly and making it as powerful as it is.

Tell us about your production team.

This was the first film I made where I didn’t know anyone in the crew going in.

I opted not to bring any of my usual (American) collaborators with me to Bosnia because I wanted to spend all the money in Bosnia, on a Bosnian crew. This was important to me, a way to give back to my community. But it was also really scary. I’m used to working with friends with whom I have a shorthand and who have my back no matter what, especially when things get tough.

Here, I had to find those friends anew and trust that a group of complete strangers would follow my lead once we got to set. I was incredibly lucky to have met the producer Kerim Masovic through Adnan Haskovic, who then introduced me to our Production and Costume Designer Adisa Vatres-Selimovic, both of whom proved almost instantly to be just the friends and collaborators that I needed, as well as incredibly good at their jobs.

To find a Bosnian DP I watched all the films and DP reels I could find, and Alen Alilovic’s style proved to be the most in line with what I wanted for this film’s visual language. We all worked together to create the world of the film, and I would be remiss not to also point out Adisa’s Art Team, including Monika Mocevic and Admir “Guma” Karkelja, Maja Talovic, our amazing Head Hair and MUA, our editor Sasa Pesevski, and our sound guys (Adis Bazdarevic, Almir Kozic, Faris Lukovac, Damir Prohic) whose talent and kindness were unmatched.

Giving it all a glorious bow on top was my good friend, and an amazing musician, Merima Kljuco, who asked to compose the music for the film the moment I told her about it, back in the research stage, and who seriously surpassed all my expectations with her beautiful score. And, of course, Azra Isakovic, who is from Herzegovina, but whom I know from Los Angeles, who helped raise the rest of the money we needed, and who came to Bosnia when we were in production to help however necessary.

Where did you shoot and for how long?

We shot on location in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina for five days total, plus a month of prep and two months of post.

You are a war refugee yourself. How much of an impact did going from one culture to the other affect you when you went to the USA?

Even though I grew up fully exposed in the US culture through movies, TV, music, and the like, coming to the USA as a refugee was such an enormous shock that it took me a good five years to even accept that we were here and not going back.

This was mainly thanks to the enormous amount of PTSD that I, and all other Bosnians, were suffering from, and which went ignored and untreated for years (and in some cases still is). I finally addressed mine some 20 years after landing on these shores, after which is when I finally started being able to love and appreciate the good stuff about this country instead of just hating it all.

Nowadays I consider myself very much a combination of these two cultures, both as a person (sunny disposition mixed with extremely dark humour), and as a filmmaker (European sensitivities and themes mixed with American commercial film structure), and am eager to tell stories that bridge this spectrum of experience.

Would you like to expand on the issues and themes explored in this film into a feature idea. Also, who and what are your key cinematic influences?

While the short was made as a stand-alone film, it also serves as a proof-of-concept for a feature version, which I realized was possible, and necessary, during the making of it. There is so much more to the story, which deserves to be told and shared on the bigger platform, and I hope we find the money to bring it to life.

As for the cinematic influences, each of my films has had its own visual inspiration, so in terms of cinematography it’s a mixed bag, but I tend to lean towards classical, both in terms of visuals and storytelling. Artists like Roger Deakins, Gregory Crewdson, Roman Polanski, Alfred Hitchcock, Pina Bausch, and Djordje Balasevic are just some who keep inspiring me over and over again, as does Vedanta philosophy, which I’ve been immersed in for the last decade.

What issues and themes would you also like to explore in future works?

Blame it on me for being a refugee who immigrated to this country at an age when I was neither a fully formed adult, nor a still-moldable child, but the theme I keep revisiting over and over again is that of identity and what it takes for us to drop the facade that was imposed on us by others, and to fully step into who we truly are.

This is tightly connected to the sense of belonging, which I myself struggle with, and therefore, by default, project into my characters as well.

In general, I’m drawn to the darker side of human nature, to the shadow-self that we hide from the world, and which tends to haunt us, one way or another, until we find a way to embrace it.

Loving this part of us is easier said than done, and so many of us do everything in our power to keep it hidden, ashamed and scared, not realizing that by ignoring it we only give it the power to destroy us when we least expect it.

My goal with my work is to help my audience learn to accept their darkness by exposing them to relatable characters who are forced to confront it in themselves, and who find their way through it, showing us it’s possible, and possibly not as scary as we think.

Tell us more about your feature documentary BACK TO BOSNIA.

This was my very first film.

I was a professional theatre director at that time, and all I knew about making a documentary was what I read in a book that I bought once I decided to do this, which basically told me to hire a professional DP, which I smartly did. Other than that, my team consisted of a theatre sound designer I was dating at the time, whom we rebranded as the one-man sound production team, and two theatre friends (an actress and a costume designer) who offered to come with me as producers, not that any of us really knew what that meant.

Furthermore, my father, who was to be the only protagonist, declared on the first day that he would talk only to me directly, not to the camera, and that we couldn’t do any second takes. This is how I, a shy introvert, ended up being in the film myself, trying to direct and participate at the same time, while also processing my own emotions, which were overwhelming, to say the least (just watch the apartment scene to see what I mean).

We spent two weeks filming everything and anything we came across, and another year and a half sifting through the footage and translating it into the film it became. It premiered at the AFI Fest and went to screen at numerous festivals around the world. It’s truly a little film that could, and I’m immensely proud of how far it came.

How has Bosnia changed over the last few years and do you go back when you can?

Post-war Bosnia is a very different place than Bosnia I grew up in.

So much so that I feel like it’s a completely different country now, one in which I feel like an alien from a planet that no longer exists. The war ended abruptly, with the signing of the Dayton Peace Accord, which basically let the Serbs keep the territories they occupied and ethnically cleansed during the war.

This is now known as Republika Srpska, and my hometown of Banja Luka is its capital. While technically still a part of Bosnia, they also have its own president and governing body, and for the most part, run that entity as its own thing. This is dangerous because they don’t teach their youth about what happened during the war (genocide denial is ever-present), and so many of the new generations are brainwashed to fear and hate “the others” who live over in the Federation part of the country (that’s primarily Bosnian Muslim and Croat), and vice versa.

It is as if the powers that were back then taken; that image of Bosnia that was sold in the media (“they’ve hated one another for thousands of years”) and crafted the new country off of that alone. I’m a proud Bosnian and I do try to go back whenever I can, but it breaks my heart to see Bosnia like this every time I go.

Bosnians at their core are tolerant, welcoming people, kind and big-hearted, no matter what ethnic and religious label anyone holds. I don’t know how we get back to those core values, but I do hope that SEVAP/MITZVAH reminds us of them, and inspires us to act as such, and to be the change we want to see in the world, as the wise man advised.

How has the festival circuit helped you?

We’ve just started our festival run, with a premiere at the Cleveland International Film Festival in March. That screening was great, and it was wonderful to see so many people love the film. We’ll see where we go next, and how it will help in the long run.

Finally, what are you most proud of about this short?

I’m immensely proud of the hard work we all put into the film, as well as the fact that its message is resonating with the audiences so far.

This is no small feat given that it asks us to remember our humanity and goodness in the world where evil prevails, which feels like a whisper in the enormous echo chamber of divisiveness, anger, and cynicism that seems to pervade our media nowadays.

Here’s hoping it inspires more people to seek that kindness in them no matter what, and that its influence continues to grow.