Kira Dane and Katelyn Rebelo have teamed up for an extraordinary new short MIZUKO (WATER CHILD), which focuses on the emotionally charged feelings of one woman who has decided to have an abortion.

Film And TV Now recently interviewed the film-makers regarding their work.

FILM AND TV NOW: The film reflects very much in a spiritual sense across two cultures the emotional trauma of what abortion – and to some degree – pregnancy represents. What was your point of origin for the short?

KIRA DANE: Mizuko is based off of my own experiences of having to get an abortion in the US, through the cultural context of Japanese-Buddhist mourning and acceptance.

The procedure itself was as simple as it could possibly be, insurance covered the bulk of the costs, and I had support that came with living in a state where it is widely accepted. At the same time, I found myself completely taken aback by how emotionally affected I was by the experience.

I had never seen it as a big deal before I had to go through it myself. So I didn’t really know what to do with myself when I realized it was a big deal for me. My resolve in my decision never faltered, and I’ve never once regretted it, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t feel confusing and painful, and it seemed like there were no systems or communities or resources to turn to with that pain. It mostly felt like I was supposed to suck it up, and I was supposed to just be grateful that I could get the procedure done in the first place.

But I’m half Japanese, and when I looked into how Japanese culture deals with abortion, I found this incredible Buddhist ritual for people who’ve had abortions called mizuko kuyo.

It didn’t dictate abortion as right or wrong, but allowed people to process and grieve the loss of these smallest forms of human life. Since the philosophies behind this ritual helped me so much, I knew it would be a really impactful story to tell in the US.

I reached out to Katelyn, who was a friend from college, where we had already collaborated on a few projects. She really believed in the potential of telling this story, and we would spend the next two and a half years hunkering down and giving our absolute all to co-producing, co-directing, co-animating, and co-editing this project.

I wrote an essay about the philosophies behind the mizuko kuyo ritual tied into my own personal experiences, and we used that as the backbone for the film.

FTVN: Elements, particularly water, play a key part of the flow of the narrative, either in terms of what the woman perceives, but also in the overall film. How does the concept of Buddhism help this?

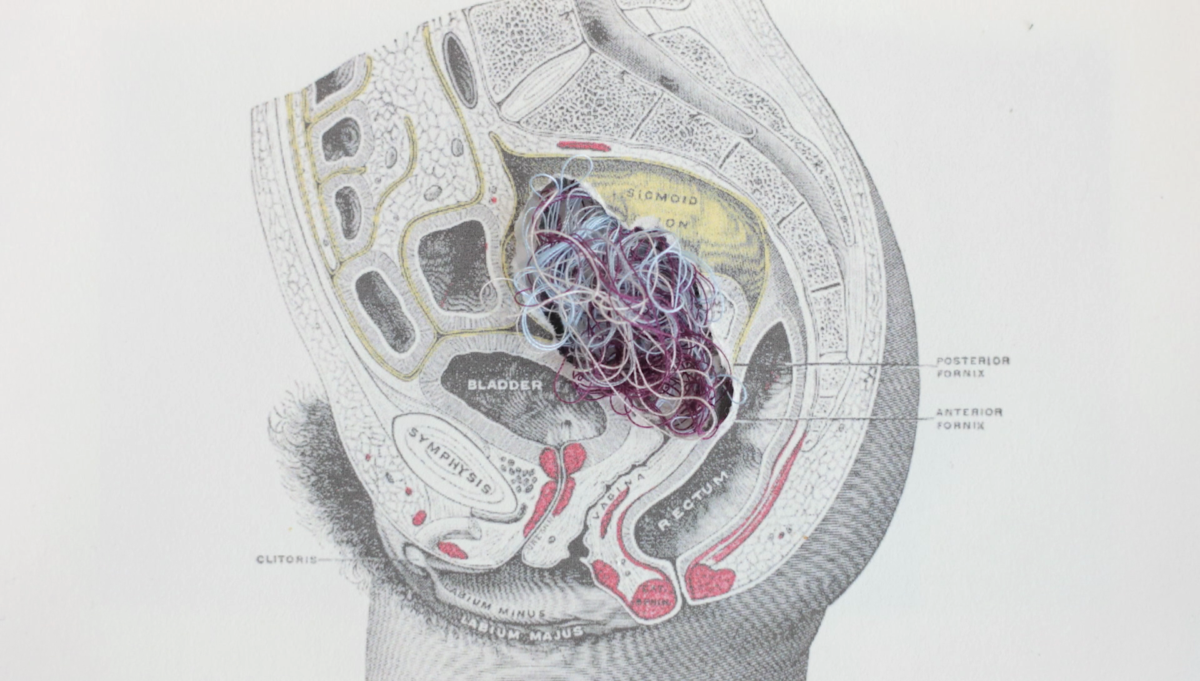

KD: A lot of Buddhist practice is centred around unifying the separate definitions you have for your mind and your body, and realizing that the idea of self is just a mental concept. One that can be broken down pretty easily, and can’t be delineated from everything else if you really examine it.

So when you think about how water is the source of all life — and how it’s the most abundant, but also the most frequently recycled element in our bodies — this division that you’ve built up between your self/body and all other life gets especially shaky. And when you realize how often you’re absorbing and releasing, destroying and rebuilding the elements that make up your body, when you know that for every human gene in our bodies, there are three-hundred and sixty microbial genes, you really start to wonder where you begin and end. Or what it means for life to begin or end.

Your own body is made up of a chaotic battlefield of constant growth and decay of living things. Buddhists have been spiritually on to all this for millennia, but it’s incredible how it aligns with everything we’ve come to understand about our bodies with modern science, physiologically. The constant, never ending tide, or the gradual pouring in and out of life that Japanese Buddhists focus on for the mizuko kuyo ritual completely makes sense with how our bodies work.

So, re-examining the political abortion debate in the US through that context — the one that is largely centred around the question of whether that undefined thing growing in a woman’s body is a valid life or not — is really limiting and one dimensional.

The main thing we hope this film incites is more conversations around abortion in the US that allow for nuance. No one wants to be in this position of having an unwanted pregnancy. But when it comes time to end a growing human life in your own body, you have to confront all these huge questions about life and death, and where we come from and where we go, in a very personal and intense way. And if we can admit that none of us truly have clear answers to that, there can be more understanding and empathy for the choices people make when they find themselves in that situation.

FTVN: You use an interesting mix of what is termed in the end credits as ‘water-colour animation’ as well as what looks like to be washed out live action footage. Was this the original visual intent when you were conceiving the short?

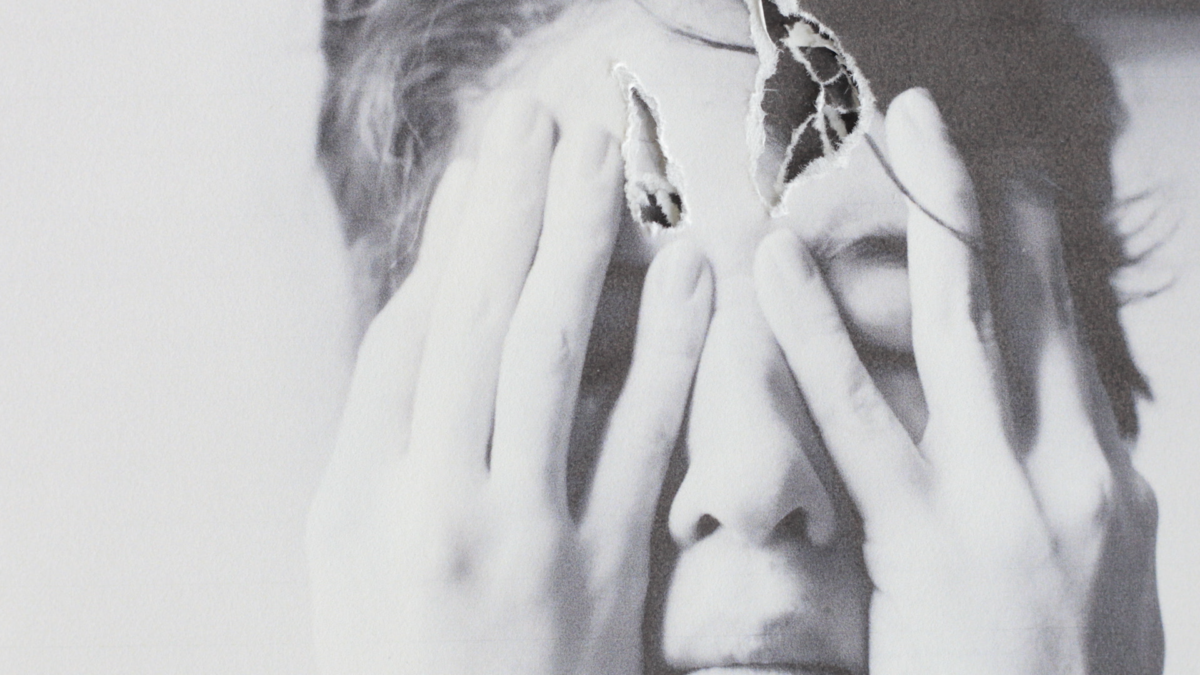

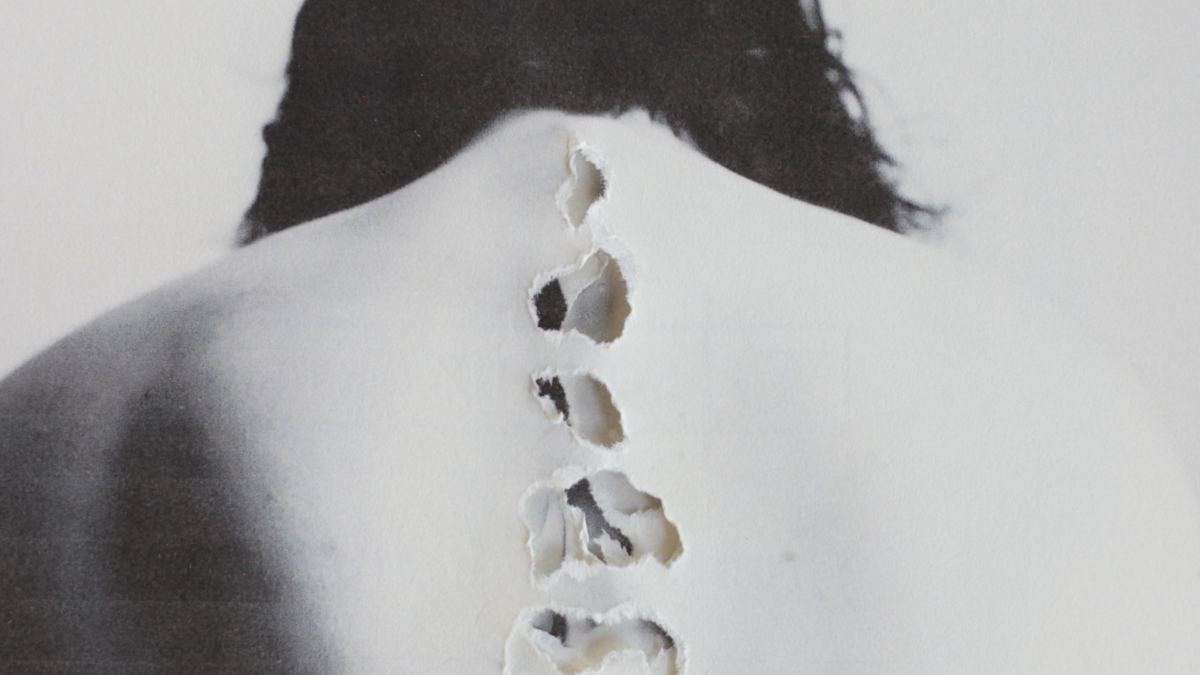

From the beginning, we knew we wanted to have two distinct visual styles that spoke to the two diverging cultures and narratives.

The English sections were meant to evoke the numb shock of discovering and choosing to end a pregnancy, and the kind of detachment of the mind from the body that not only comes from having an abortion, but also from living and growing up in a city as large and impersonal as New York. To do this we wanted the visuals to be gritty, dry, and almost unnerving at points.

The Japanese sections were rooted in Kira’s childhood memories of spending time by the ocean in Japan. The colorful memories of childhood were supposed to represent the kind of assurance in your own body that you have when you’re in nature, and when you’re little.

We wanted it to act as a deep contrast to the harsh realities of abortion and adulthood, when so many people lose the connection they have to their bodies . When we started the project, we knew that we wanted these two opposing styles and stories to merge together at the end of the film. but figuring out exactly how to do that was an ongoing process.

FTVN: Tell us about your production team.

We knew this was going to be an intimate story to tell, and decided the process should feel as intimate as the final film.

To do that, we decided we’d have a small team of people and take on a lot of the work ourselves, co-directing, co-animating, co-producing, and co-editing. We were very lucky to work with some incredibly talented animators, Joyce Zhao and Melissa Garvin (who were both working remotely) as well as our animation assistant Zoya To.

Midori Hirano was our composer, who we actually reached out to after listening to her music while working on the animation in our studio. The final track in the film The stars vs creatures by Colleen also came up from our studio playlist.

Our friend Gretta Wilson worked as our associate producer for the live action shoots in New York, and it was so helpful to have her there and help us navigate the details of production. For post production, we had free services from a post-house called Sim in New York, as part of our grant package from Tribeca. It was really helpful in shaping up the quality of the film in a way we never would have been able to do on our own.

FTVN: You had help from Tribeca in terms of getting the film off the ground. Tell us more about how this organisation aids film-makers in realising their filmic ambitions.

In all honesty, this film wouldn’t have been made at all without the support of Tribeca. We had just graduated college when we started making Mizuko, and didn’t really have any external resources, previous work to show, or any funding at all. Tribeca Film Institute still believed in the film, and took a chance on us as film-makers, despite all of that.

Not only did they give us the grant , but they also provided close mentorship throughout the entire process. We recently found out TFI and all of their programs have been shut down due to budget cuts from Covid-19, which is devastating for the entire independent film community. The work they did was so powerful in creating a platform for under-represented and emerging film-makers, and it’s scary to think about the vacuum their absence will create.

FTVN: Has the film been screened for anti and pro-abortion charities and how do you feel the film will help women who are going through the difficulties of this?

We haven’t held specific screenings for either anti or pro abortion charities yet, but throughout the process of making the film it was really important for us to listen to a wide range of opinions and get feedback from people who fall around and between both “pro-life” and “pro-choice” opinions.

We wanted to create a space for people to feel comfort in grieving, and vulnerability, and the ability to emotionally process an experience that is so politicized, and often categorized as “just another surgical procedure” or “murder” and nothing in between. Some of the research we had done before we started making this was looking into personal narratives of people moving between being “pro-life” and “pro-choice” in the US.

A pretty consistent experience we noticed was people becoming “pro-life” only after having an abortion themselves. There were so many stories of people feeling immense sadness or guilt after having an abortion, and we thought a reason they turn to being against abortion entirely is because there aren’t really any resources or outlets to understand these emotions outside of the anti-abortion rhetoric.

And at a very basic level what we wanted to say with Mizuko is, it’s okay to feel! It’s okay to grieve if you need to. Having an abortion is made up of so many personal and individual decisions, and we should allow space for these emotions in a way that doesn’t judge someone else’s choice.

FTVN: How long did it take to complete?

All together, the film took around two and a half years to complete. The first half of that was mostly used for research, writing, and testing animation styles — which was all happening while we were working on other jobs and projects, and trying to figure out how we were going to find the time and money to make this.

We couldn’t really focus on it full time until we got the grant, and then we spent almost a full year in production, which included all of the animation and shoots in both New York and Japan.

FTVN: How has being a Fellow of the Sundance Ignite Program influenced your creative ambitions?

KD: Sundance Ignite happened when I was feeling really lost and unsure of myself in the year after graduating college. My friend calls it the (minimum) 1-year, mandatory post-graduation flail. I was deep in that.

I had wanted to be a film-maker for as long as I could remember, but I was at the point where I was really questioning the feasibility of it. I’ve never been a very pushy person, but you have to do so much pushing and fighting to keep your head above water in this career, and I was really questioning whether or not I was resilient enough to keep doing it. So being part of Ignite boosted me up into that breathing space when I really needed it, where I could feel inspired and accepted and valued in what is normally such a competitive, cut-throat industry.

FTVN: You achieved a Minor in Social & Cultural Analysis at Tisch. How has this influenced the direction of your film-making ambitions?

KATELYN REBELO: I think it influenced the way I approach film-making in more ways than I realized at the time. The classes I took were actually outside of Tisch, and I became interested in the program because I felt like something was lacking within the film department.

In the film classes it seemed like people were taught how to use a camera, sound equipment, and the right way to format a script, but nobody was talking about or questioning the power a camera holds, and the responsibility a film-maker has in the stories they share. Taking these other classes not only influenced the way I research a project before going into it, but also taught me to rethink representation within media and the ethics of storytelling.

FTVN: Is the subject matter in this short film something you’d both like to expand into a feature film or documentary subject?

When we first started this, the initial intention was to make a feature film that included personal stories of abortion through the context of different cultures around the world. We realized pretty quickly how difficult this would be for the point we were in our careers.

We also realized there was so much to explore within the culture of mizuko kuyo and Kira’s personal story, and that it was necessary to narrow that scope in order to do it properly. It took a lot out of us just to make this short, but on the other hand, there’s still so much we weren’t able to address in a fifteen-minute film.

We’re open to expanding the ideas in Mizuko into a feature — it could take form in so many different possible ways, and it would probably be dramatically different from the short. We would need the right resources and time, but there’s definitely more story to tell there.

FTVN: Finally, what are you each most proud of about the film?

KR: This is such a hard question. I think Kira and I are both very critical of our own work, so it’s almost easier to describe things we dislike about the final film instead of things we’re proud of.

Overall though, I’m happy we were able to move away from more traditional methods of documentary storytelling, and still create something that is informative while also emotionally healing. One of the best parts of sharing the film has been the people who come up to us after screenings, or reach out to us and share their own stories and talk about the impact Mizuko has had on them.

All we really hoped for when we started working on this was that someone would see it and feel more comfort in their own experience, so I’m proud we were able to achieve that.

KD: I would pretty much just echo everything Katelyn said — it’s hard not to zero in on mistakes here and there, but I think we were able to accomplish so much with the time and resources that we had. And given the circumstances, the fact that we were able to pull this off at all makes me proud.

The best, best feeling, like Katelyn mentioned, is when it really resonates with people and they reach out to tell us how much they connected to it. I think we were able to do a good job at navigating the line between a film that’s polished enough to be absorbed by a large audience, but at the same time ‘home-made’ enough that it’s accessible and genuine to who we are.