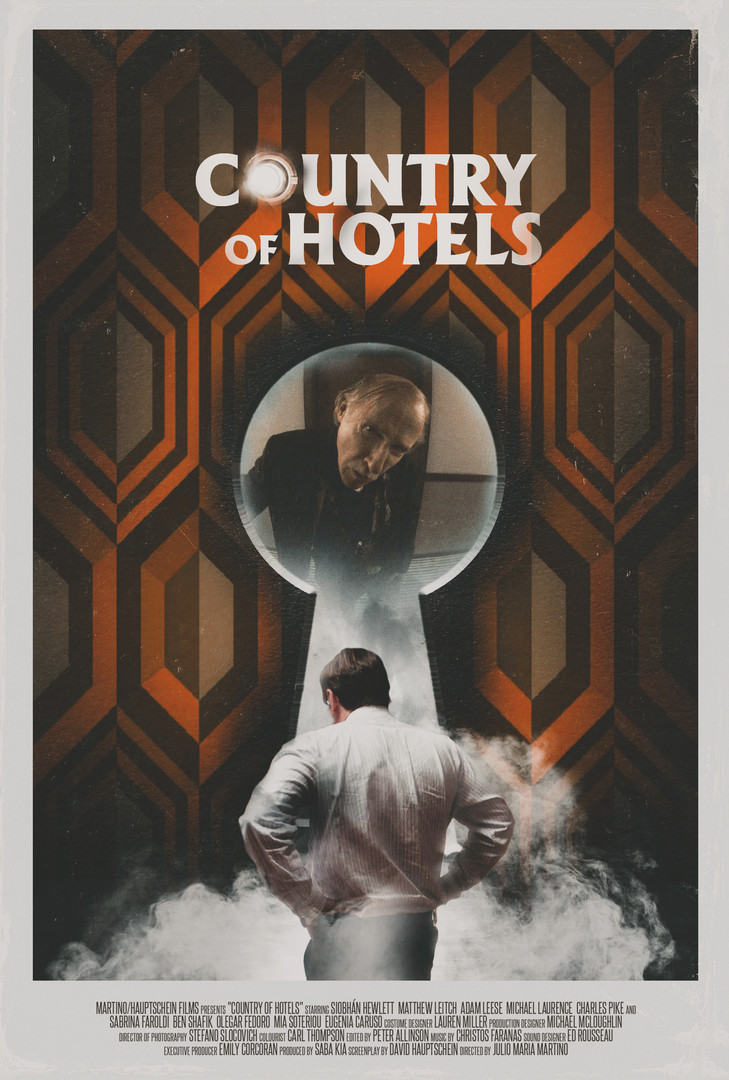

Julio Maria Martino reflects on multiple lives at a stranger than strange hotel in his new indie film COUNTRY OF HOTELS.

Film And TV Now spoke with the film-maker about the process and his collaboration with writer David Hauptschein.

FILM AND TV NOW: The film clearly is a strange and weird mix of the supernatural and surreal as we delve into the entwined lives of those who come to stay at room 508. What was the inspiration for the film?

JULIO MARIA MARTINO: When David Hauptschein (who wrote the screenplay) and I were first talking about making this film we hit upon the idea of a hotel as a single, simple location where we could tell a lot of different stories.

We also had to reckon with the fact that if we were going to make a film, it would have to be very low budget, as we knew that no film company or funding body was going to give us money to make the kind of film we wanted to make. So we came up with the idea to make a film set around a single room in a mysterious hotel, and tell the stories of the grim and bizarre goings on in that room.

A hotel, cinematically (and also in literature and music) is a very evocative location. Hotels are places where you can suddenly find yourself out of your element, somewhere that feels both familiar and yet strange at the same time.

You can step into a hotel room and really have no idea of what went on there the week beforehand; maybe a couple was having an affair; maybe someone got drunk, passed out and banged their head on the bathtub; maybe someone got murdered; or maybe someone went quietly insane. Apart from a near invisible trace, almost nothing remains of this prior guest.

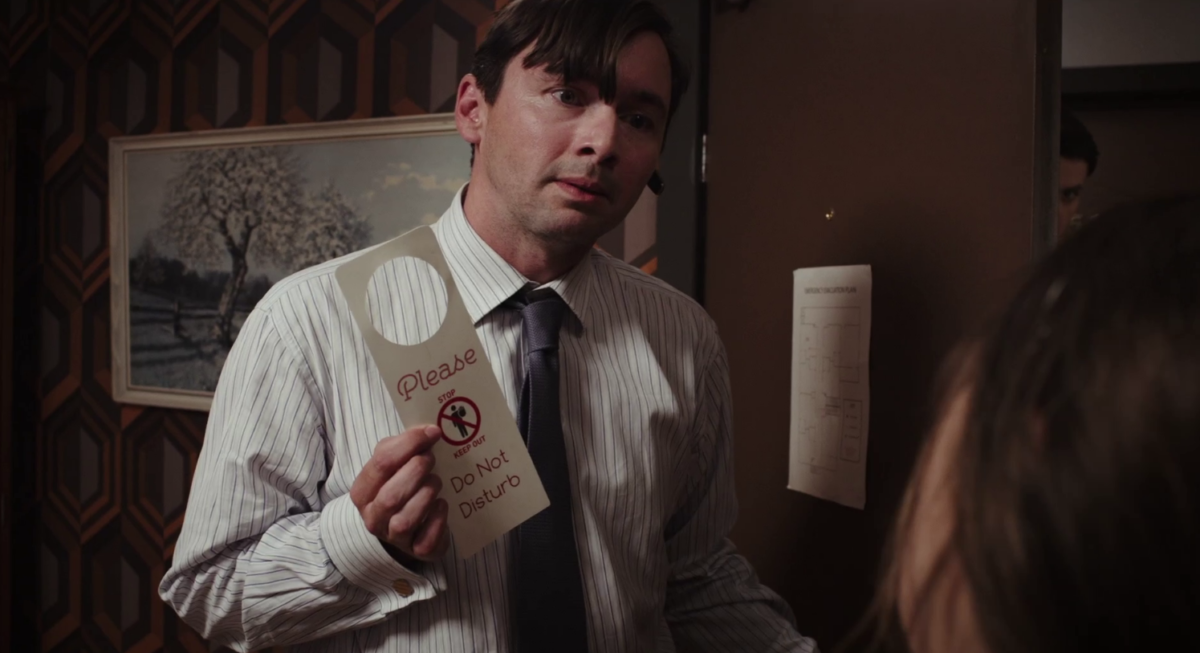

We thought the hotel room could act almost like a principal character, an antagonist to the film’s various protagonists. i.e. the guests who stayed there.

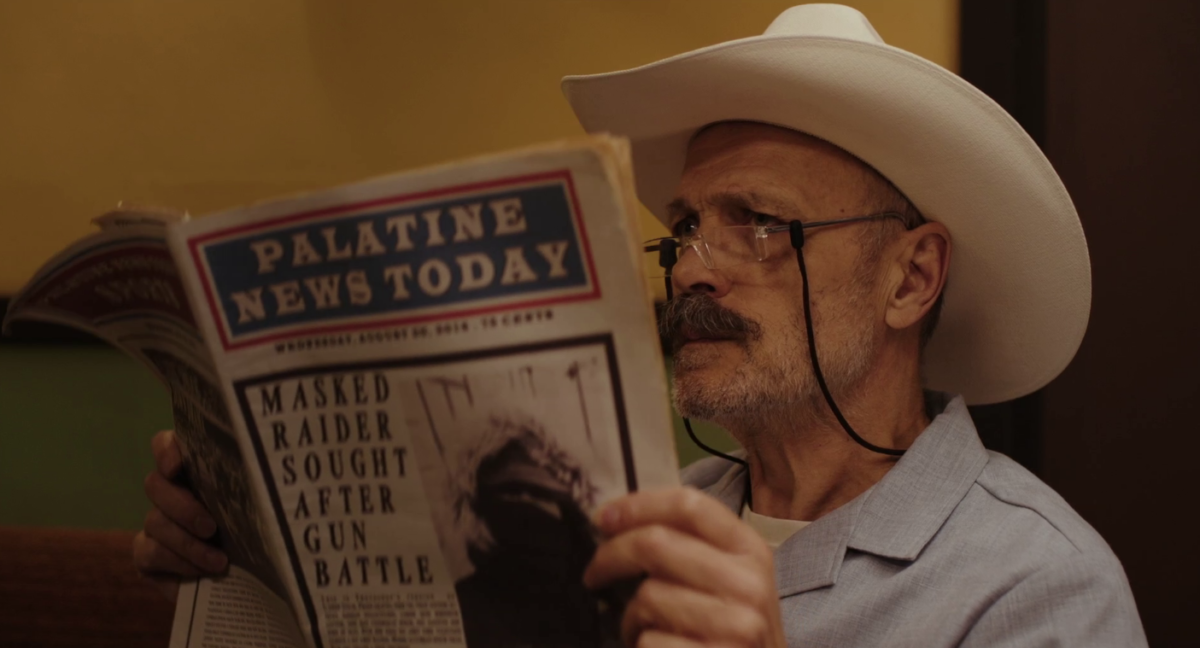

At the start we thought we might make a short film, or perhaps a series of thematically linked short films which were all set in the same hotel room. But, little by little, the idea developed until it became a feature film, mostly set within the confines of a single hotel room, plus a few supplementary locations: the corridor outside the room, the hotel lobby; and some curious places seen on Room 508’s television.

FTVN: COUNTRY OF HOTELS is a debut film. What other projects did you consider before making this one your first?

JMM: Although I had always wanted to make films, I don’t think I really considered any film projects seriously before embarking on COUNTRY OF HOTELS. Looking back, my ideas prior to this experience were always too nebulous and unfocused. However, on finishing COUNTRY OF HOTELS I have found myself full of very concrete ideas for new films.

FTVN: Influences that come to mind are BARTON FINK, 1408 and Stanley Kubrick’s film version of THE SHINING. When you were conceiving the film, what other cinematic influences came into the fray?

JMM: In preparation for making the film, I studied several films which had long been an inspiration to me, and which also had much of their dramas set in tightly enclosed locations. Indeed BARTON FINK was one of them, but also Polanski’s THE TENANT and ROSEMARY’S BABY.

With regard to Polanski (along with David Lynch) I don’t think there has been a better director for filming “dreams” or a “dream state” and generating a sense of the uncanny. Apart from a couple of moments, I tried to avoid jump scares, and use more subtle means to destabilise the viewer. REAR WINDOW was a huge inspiration and resource for me, in the way it dramatised so much of its story within the confines of Jimmy Stewart’s living room.

Some people who have seen the film say that the wallpaper in Room 508 reminds them of the carpet in THE SHINING, and I agree it’s similar. I chose it because our Production Designer Mike Mcloughlin, who was brilliantly resourceful on very limited means, showed me a handful of samples ten days before we were about to start shooting.

I had to make the decision that day and we didn’t have time for any mistakes. So, I chose the best wallpaper; it had a puzzle element to it and the colours evoked the right world. However I purposely didn’t watch or study THE SHINING in advance of making COUNTRY OF HOTELS because it’s such a totemic film and Kubrick is such an iconic director.

FTVN: Tell us about your cast.

JMM: I already knew about half the cast prior to shooting, as either friends and people I had worked with closely before (when I was a theatre director). By choosing people I knew and trusted, I felt free to be playful and to come up with innovative ideas.

The first thing we shot was the stand-up comedian who appears on the television. He is played by Colm Gormley, an actor I have known since we were at University together. From the second take onwards I encouraged him to improvise and he started to come up with really funny, interesting stuff, a lot of which ended up in the finished film. (NB: With regard to improvisation, I always try to keep the focus of the improvisation within the world of the film). So, when you hear him riffing, about taking himself out on a date, giving himself a cuddle and then having sex with himself, that is all Colm’s improvisation.

Both the writer, David, and I really approved of this inventiveness and we kept it in the film; I think it acts as a doorway into the film’s more surreal and unpredictable elements (it also highlights the theme of narcissism which is very important).

The main actors (Hotel Guests, Staff etc) were made up of actors David and I already knew; or people who were recommended to me by our Executive Producer Emily Corcoran (who has a lot of experience in independent film-making); and also some people who came from a casting call we put out. Everyone I didn’t know beforehand, I auditioned one way or the other; some in person and some via Skype (as they were working elsewhere).

For a film like COUNTRY OF HOTELS, I think it’s important to make sure that the actors can tap into the absurdity of the situation. It’s usually the case that if the actor understands the black humour / absurdist elements of the script, then we’ll have little problem working together. One final thing to say about auditions – I always try to select pieces of the script which include the “extremities” of the piece.

In COUNTRY OF HOTELS, several of the characters have to venture into the territory of abnormal psychological behaviour, and so I always asked them to read from something which demonstrated to me that they were both comfortable and capable of operating in that zone.

FTVN: Tell us about your production team.

JMM: I could speak for hours about how great each member of the production team was – there were no weak links. Like the cast, the production team was a mix of people I knew or had come across myself; and people who were recommended to me by my producer Saba Kia and executive producer Emily Corcoran.

One of the most important relationships was with Stefano Slocovich, the DOP. We were both “first timers”, Stefano had never DOP’d a feature before, but within a couple of days it was clear that he was in complete control of the situation. He worked brilliantly with the camera crew, even though his English is far from perfect: Italian is his first language.

Because I can speak Italian we were able to converse privately at first for each set-up, and then relay our decisions to the crew. This became quite an effective method of retaining control in the challenging environment of making a debut feature, where you are surrounded by people who have done this hundreds of times before.

Another of the areas I’m most proud of was the way the score (by Christos Fanaras) and Sound Design (by Ed Rousseau) worked so well together. Christos was someone I had seen playing in a band at the ICA in London in 2010. We got to know each other and I realised he also composed this amazing music which I felt would be really suited to the world of COUNTRY OF HOTELS. Christos had never composed a soundtrack before and yet I think the music he created for the film is brilliant and iconic. It gives the film (and the world of the hotel, primarily) and very idiosyncratic and unique identity.

Finally, the relationship with the editor Peter Allinson ended up being a truly epic affair. We had originally planned on editing the film over the period of two to three months. We ended up working on the edit of the film for a little over two years!

There were some practical reasons for this (neither of us could afford to work on the film full time) but it was also because we entered a zone of continually challenging each other to improve the film. I’m really glad we worked on it for as long as we did, because (as well as learning a lot and forging a great friendship) we managed to create an unusual, hallucinatory rhythm to the piece, which would have been impossible had we knocked it together in a couple of months.

FTVN: Where did you shoot and for how long?

JMM: The film was made almost entirely on built sets, rather than found locations.

My producer, Saba Kia, did an amazing job of finding a very accommodating warehouse in a place near Basildon in Essex, about an hour’s drive out of London. We filmed in the warehouse over a period of about 20 days.

The warehouse was partially in use while we filmed. There was a crew of around 10 people packing trainers and sport shirts into boxes, while we occupied a 200 square foot platform at one end. So every time we wanted to shoot we’d sound a horn and the workers would pause work while we filmed.

When I called cut, another horn would sound and they would start work again. This sounds crazy, but it actually worked well and we became very friendly with the warehouse personnel. The sets were designed and built by our production designer Mike McLoughlin and his team, rather than “found locations”.

Filming on sets allowed us much greater control over shot choices. We could remove walls and film from above (ie we could shoot through walls and ceilings), and so create more of a sense of distance in what was supposed to be a very small hotel room or narrow corridor. This was important not just from a technical point of view, but it also stopped the film from becoming visually repetitive and allowed it to “breathe”.

If we were using real locations, our shot choices would have become incredibly limited and the film would have been claustrophobic and oppressive in the wrong way. Filming on sets gave us a much more cinematic look and feel.

It is gratifying when people who have seen the film ask me where we found the locations and if we used a real hotel. It means the film is convincing at a visual level. We constructed an artificial world, and we didn’t aim for naturalism, yet still wanted it to feel real to the viewer.

Creating a credible “consensus reality” in a film like COUNTRY OF HOTELS is critical for the film to work. If your foundations are solid, then you can convincingly make the journey into the surreal.

FTVN: How did you raise finance for the film?

JMM: The budget for the film was under £100,000 including the British Film tax rebate. The money was raised through private investors. Unfortunately, I think the kind of films we want to make are never going to be of interest to arts funding bodies.

Because the production was initiated by the writer David Hauptschein (who lives in Chicago) and myself, we were able to call on people in the US, the UK and also in Italy where I have a lot of contacts.

FTVN: Did you storyboard the film before and during production?

JMM: No, we didn’t storyboard a thing. But the DOP, Stefano Slocovich, and I spent a long time devising shots and working on our shot list; so we had detailed written descriptions for each shot we planned. For some reason this just seemed easier and better than visual storyboards.

I’ve known Stefano for many years and so we were able to spend a period of several months prior to shooting coming up with ideas and devising our shot list. Throughout the shoot we carried on revising and updating it every night after work.. We’d be on set for 7am, finish shooting around 5 or 6pm, take an hour off for dinner and then we’d keep on working on the shot list for the following day until midnight or beyond.

FTVN: What makes you as a director/writer team work so well together?

JMM: I’m glad you think we work well together!

David and I have known each other for over 20 years and in that time I’ve directed 9 of his plays. I think, at heart, we both believe that the challenges of collaboration make for stronger work. As director, I had final say over the finished film, but David and I were discussing it right up to the moment the colour grade was locked.

If the film has a singularity of vision (which I think it does) then it’s because we tried to create a world which exists independently of its creators. The mysteries of Room 508 are to be found within its walls; the writer and director don’t have the answers.

FTVN: Given the effect the global situation has had on theatres, where do you see live performance evolving in the ‘New Normal’?

JMM: What I see is this: there is a very visible, unending march, towards not only “streaming” but an entire society which tells you that you can get everything you could possibly want, without needing to leave your living room.

Cinema, music, even theatre, visual art, museum tours etc, also food, and even sex. There are all sorts of reasons why this isn’t desirable at all, and must be resisted, even if there are too few people in the “resistance” at the moment. When this is all over, we need to get out doors again, and experience culture out of our own living rooms with all the necessary difficulties and time constraints that it imposes on us.

We need to make the decision to commit to watching things again outside of our houses, booking tickets and sitting in auditoriums etc. I think the march towards “staying in”, even after the pandemic is over, won’t stop accelerating. But I do see signs that there is a sizeable minority of people who realise they need to mix it up once or twice a week and leave their living rooms to get their culture.

One example: I’ve noticed in London (and throughout the UK) that there has been a huge growth of showing silent films with live musical accompaniment. It’s an experience you really cannot fully replicate online. It’s a recorded experience (the film) augmented by a live, improvised, performance (the music).

Before the pandemic hit you could go to a silent film even almost every night of the week in London; the calendar was packed with these events. It’s one sign of many, to me, that a significant minority of people are hungry to get out and experience culture in a room with other people they don’t know.

FTVN: The film is receiving its European Premiere at Manchester Film Festival. What has the overall reaction been like for the film so far?

JMM: The best responses, for me, have been from people who were profoundly unsettled by the film, and intrigued by its mystery. Quite a few people who have watched it have described it as “unbearably tense”.

One person told me that all along she assumed The Maid was a malicious character, maybe even evil and in league with the rest of the hotel staff. But, suddenly, at the very end, she felt a great pity for her.

I don’t expect everyone watching the film to feel this way, but that sadness regarding The Maid was definitely something that we intended. We tried to build her story very subtly, so that she was almost unnoticeable as an important character until the very end.

Any response which suggests the viewer carried on following the journey of the characters, and their various plights, to the end is great; anything which suggests to me that the world of the film is still circulating in their imagination the following day is wonderful. Our aim was to create an enduring mystery which you can return to again and again.

I think for people who are looking for straight horror, where the mystery is explained, and which is reliant on traditional jump scares, the film is unlikely to work.

FTVN: What issues and themes would you like to explore in future works?

JMM: I’m not at all interested in making films where the underlying ‘issues” can easily be detected by the viewer and / or critics. There are so many people already involved in making “realistic” cinema with clear social and / or political motives, that I can’t get excited about doing that kind of thing.

I’m interested in plunging the viewer into worlds that don’t quite make sense, and communicate with their unconscious, and much as their conscious minds.

FTVN: How has the global situation affected your development and evolution as film-makers?

JMM: I think one of the biggest problems for me is not being able to see the film play on a cinema screen at a festival, in front of strangers. Exposing a new film to an audience (not a series of individuals on their sofas at home) is an incredibly important right of passage for a film and the film-maker.

One tiny example: someone in an audience may laugh at a moment no one else found funny, and this may “teach” (or indeed challenge) the rest of the audience to appreciate that what they are watching is actually funny; perhaps a film with a sly sense of humour they hadn’t picked up on until that moment.

This act of a single laugh by one audience member can fundamentally change the whole course of a film. And there are a whole load of positive restrictions that being in a cinema places on an audience. You can’t pause the film; you can’t switch it over; you can’t (easily) look at your phone.

Also you’ve paid for your ticket (rather than a monthly subscription payment silently dropping out of your bank account) so you are more inclined to take the experience seriously, to concentrate and not give up on the film. As Frank Zappa said “With art, context is everything.”

FTVN: Finally, what are you most proud of about the film?

JMM: I’m proud that, for some people, the film unsettles and challenges them, and they find it a unique and idiosyncratic experience. Although there are similarities with other films, it doesn’t follow standard genre and story templates. It’s not a minimalist film or a naturalistic film: it is its own beast.