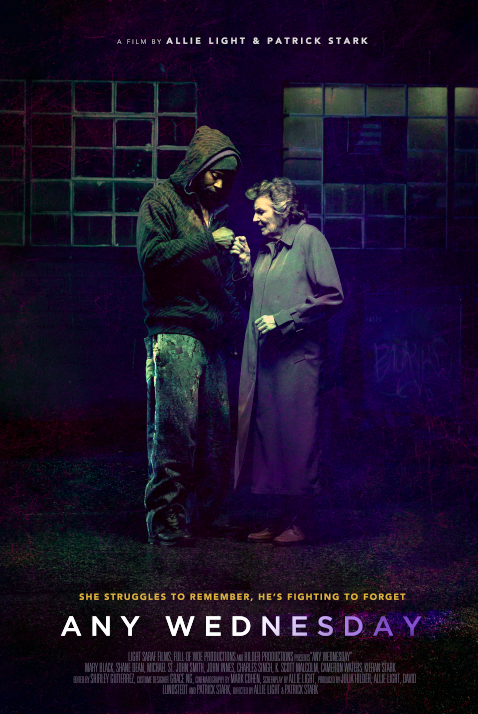

Allie Light is co-director of the fascinating short ANY WEDNESDAY, which focuses on the brief but bonding relationship between a homeless war veteran traumatised and an elderly woman affected by dementia.

Here she reflects on her various experiences:

FILM AND TV NOW: You have won major awards for your documentary work. Tell us about some of your experiences doing these and how easy was it for you to make the transition to a more narrative piece?

ALLIE LIGHT: Because my partner and I were independents and raised our own money, we were not for hire. We chose our projects and worked on our own time frame. There were some films that we sold for broadcast before we had finished and then we had deadlines. Our choices were made on: Is the project absorbing enough to hold our interest for one, three or five years that it might take to complete?

Almost always our films had personal beginnings. My first film, Self Health, was how a woman could do her own cervical exam and, with the help of other women, understand the workings and needs of our bodies.

I made this film because I wanted to learn how to do a self-exam, but I was too shy to walk into a woman’s clinic on my own. I wasn’t too shy to bring a photographer and sound recordist to make a film.

That film went to Toronto Film Fest, was translated into Japanese, was shown in Moscow (where a woman threw up after viewing the vaginal walls and cervix of the female body). The film had wide distribution and much success. But we shot it on reversal film (to better capture low light) and nearly 50 years later it has faded to a deep pink and the images are gone. Just as the present disappears into the past, so film disappears also.

Each film taught us about ourselves and the people we filmed. Our film Mitsuye and Nellie, Asian American Poets (90 min. PBS) had scenes where Mitsuye was incarcerated in a U.S. Relocation Camp for Japanese Americans during World War II. We went to Minidoka, Idaho to film there and found that the camp was long demolished and the barracks, in which people lived, had been taken by local farmers for storage sheds and chicken houses. I knocked on doors next to chained dogs to ask permission to film these buildings on private land.

We were met with kindness and generosity. Some farmers had made maps of the camp with drawings of the numbered barracks. Mitsuye was respectfully asked to autograph the square where her family had endured so much in 1941. On that shoot we struggled with Mitsuye’s restraint on camera. The shock of being in that location again, the anguish of the past shut her down. She could respond only in cliché and shallow descriptions.

I was a novice director and feared to press her too much. However, her teen-age daughter, Hedi, was with us. We tried another interview with the two of them and suddenly Hedi said to her mother, “Now I understand why you overprotect me because you know what it feels like when someone calls you a Jap.”

Mitsuye broke into tears and wept in her daughter’s arms. Hedi’s words opened a floodgate we couldn’t have known to do.

As my film-making process developed and I thought more about the content of our films, I came upon the phrase ‘The Privileged Moment’ and I realized that is what had happened in the above scene.

Francois Truffaut defined the Privileged Moment as “those quick flashes of real life that emerge briefly through the veil of cinematic artifice.” Hedi had provided the ‘real life moments’ that connected her mother to the past so that she could respond to us and our camera.

Another Privileged Moment occurred on a film for HBO about breast cancer. One of our subjects, 32-year-old Jenny was near death. As she was put onto a mattress in her father’s van, my partner, Irving Saraf and I were in the open sliding doorway, he with the camera, I with the mic on a short boom above him. She turned her head to us and said, “Goodbye Irving, goodbye Allie.”

I was overcome with a storm of silent, drenching tears. We stepped back from the van, the doors closed and the van rolled down the driveway. We filmed the back as they drove away and then swung the camera to the top of the driveway where her friends were hugging one another and crying.

We put those three shots into the film. And then one day someone said to us, “You know that scene in the rain?” We didn’t have a rainy scene. We went back and looked at the film and when the camera swung around to her friends, it was a western shot and the sun lit up the lens and my tears were moving across the entire shot, they had fallen on the lens in the van and when the sun hit the lens, the tears became rain. It was a Privileged Moment–real life poking into artifice created by us, the filmmakers.

We spent five years making our Oscar winning film, In The Shadow of The Stars, and the inspiration for that film came from my life. My first husband was an opera singer with the San Francisco Opera Chorus. He, like most singers with grand voices, wanted to be a soloist—a star. He died of cancer at the age of 33.

During his years with the opera he had taken a small silent Bolex movie camera on stage under his costume and, during the late 50s and early 60s, he filmed the great stars from a chorister’s position. The black and white silent footage was mesmerizing. Irving and I always said that we should do something with it and, finally, in the 1980s we did.

We built our movie around the old footage and made a film about choristers who want to be stars. It’s about all of us who desire a moment alone on stage. We got our moment when we won our Oscars.

Making the opera film made it easier, after Irving’s death, for me to transition to narrative film-making. The singers were actors and were exciting to work with. They loved the camera and they performed to it. We scripted parts of the film to include a soprano tea-party where they could say they were song-birds of the opera and they could sing.

We shot a high-note contest for the tenors, which was like directing a drama. It made us hungry to switch to narrative. At one point in our long documentary history, Irving once said, (probably out of documentary frustration), “If you want to tell the truth, write a script and hire some actors.” So, I did.

FTVN: How does the dynamic of co-directing a short change when you compare it to working on your own as sole director?.

AL: I have never been a solo director. I love working with another person. Probably because Irving was my partner in both love and the movies, co-directing was fulfilling, exciting and double well-done. We watched one another’s backs. We caught things the other missed. We celebrated for two and had someone to clink glasses with, jump up and down and kiss when we won.

When Vincent Canby of the New York times gave the film a top review, we danced around the house with our dog barking at the top of his muzzle. Who would ever want to dance alone to a good review? When we won our Oscars, I was running down the aisle behind him, and I said to his back, “Did you take your heart medication?” And when we woke up the next morning in the hotel and the two Golden Boys were looking at us from the dresser, we could hug one another and say, “It really happened.” Life was excellent.

FTVN: You worked with Julia Hilder as Producer, somebody who came from a Journalism background in other media, including working in Houston as an anchorperson. How much of an influence does she have on the creative process when you make a film like ANY WEDNESDAY?

AL: Truth first: Julia Hilder is my daughter. She has been a producer on Irving’s and my films in the past and now on Any Wednesday. She and I will direct together on our next film. Julia added to the creative process on Any Wednesday first by bringing her camera and documenting the making of the film. She interviewed Patrick and me; she interviewed Mary Black and Shane Dean.

Her video shows how the rain towers worked and how we made the car look like it was moving. It never moved when Mary (Agnes) was behind the wheel. She captured behind the scenes. She was also creative as additional photographer. She and our other producer, David Lundstedt (her husband), shot all the rain that appears in the windshield shots. They filmed Hurricane Harvey from their car in Austin TX and we dropped the shots in during editing.

Julia helped make casting choices. During post production, she came to San Francisco from her home in Austin, TX to look at cuts of the film, to comment and to suggest changes. Her years in television news contributed to the creative process in making Any Wednesday. Her journalism fingerprints are there.

FTVN: Tell us about how you work and develop projects as a writer and director.

AL: This project is different than the work process of documentary film, though all films I’ve created, or helped to create, had a personal beginning. In 2013 I was grieving the death of my partner. Grief consumes. Waking or sleeping, you can’t escape So, I wrote four scripts on the subject of Grief and Desire in Old Age.

Each story is different, but they have common attributes. I want to create characters who are old, exciting and interesting–who are still very much alive. I am the person to do this because I enjoy old age (except for the loss of those I love), and I can write the dialogue. I have more story ideas than I know what to do with. These four stories, of which Any Wednesday is the first, were all for short films, I was going to put them together as a portmanteau film, but it didn’t look like I could raise the money.

So, when the chance to make one came, I went with it. I have now expanded the other stories. They are no longer shorts. I talked about using grief as a subject at a Q&A after a screening, and I received an email from an audience member that said, “We were deeply moved when Agnes answered C’Mo’s question about how to remember him: ‘Grief.’ It was a startling revelation of your themes. You have transformed grief into art in this film…” Responses like this are gifts.

All I can say about my process as a director, is that it is new to me to direct actors. I like it and I find it fairly easy. I think the many years of learning how to do a good interview, how to really listen to the words of others, and then to edit sound and image–which means that you listen to the words over and over until they are embedded in your mind—makes you a good writer of spoken language and leads you into a more focused kind of directing.

FTVN: You have been very successful in both Film and Television and today it seems that the mediums seem to be changing pace with the advent of streaming and outlets like Netflix now focusing on bigger scale projects. How do you see the two medium panning out on the future?

AL: For the Audience: More variety in content in both film and TV and better access to both. Film and television mediums are often branches of the same companies (Amazon and Netflix). I don’t know what this means for the independent filmmaker who struggles for recognition from these industries, and hopes for a place at the table.

FTVN: What would you say was the most satisfying thing to have come out of making this particular short film?

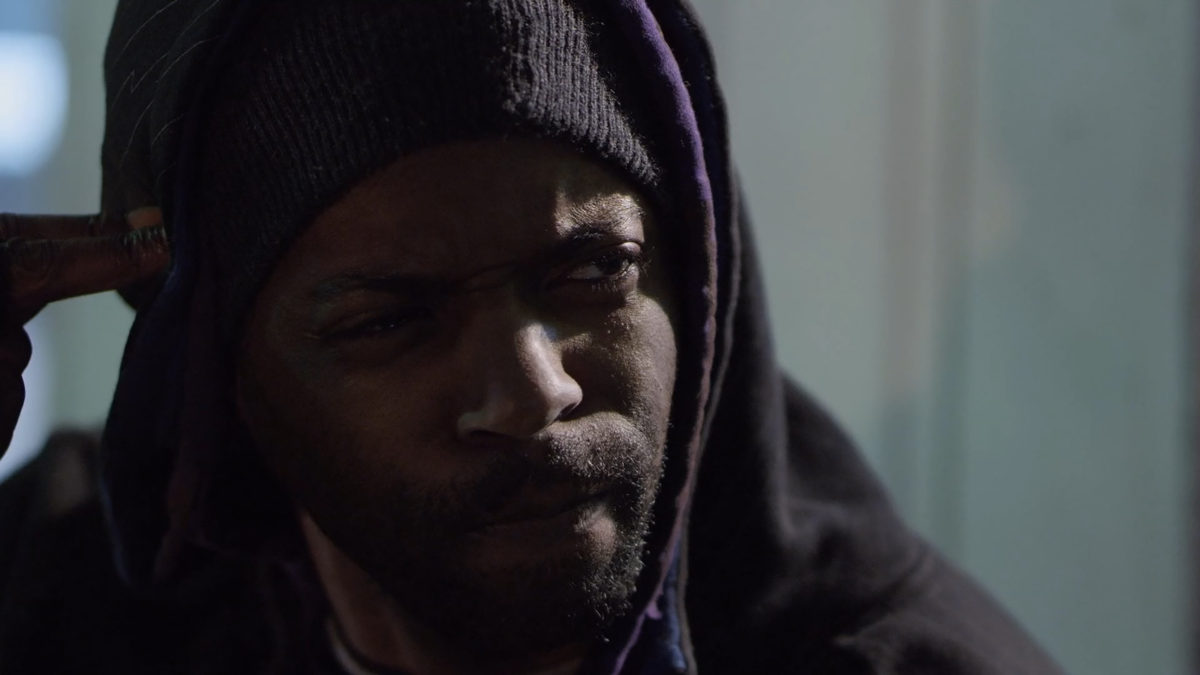

AL: I created C’Mo. I made him up. I wrote a voice for him, I created action for him–more than that I made him active. I gave him a life and words that connected to Agnes’ life. When I wrote the character of Agnes, I had a prototype: the mother of my son-in-law. But C’Mo had no one.

He was an orphan of my imagination. Not long ago I was driving in San Francisco and I saw a young African-American man standing on a street corner. He wore baggy pants and a hoodie with a hat under the hood, and he reminded me of C’Mo. As I drove on, I said, out loud to myself, “Allie, you did good. You invented C’Mo.” I have never said such a thing—or even thought it—about myself. But I said it then.

FTVN: In terms of female directors working in Hollywood and internationally today, do you feel that the sands are shifting further along in light of how things have transpired in this post #MeToo and Time’s Up revelation and revolution?

AL: A few women in the past who wanted to direct a film–wanted to bring a story to life–have done it. From Ida Lupino to Jane Campion, women have pushed to create images and stories and turn them into films. They’ve done it with no help, no support, no encouragement and little money.

Empathy on film is a woman’s stronghold. We want to realize our POV, our perspective, our feelings about life and put them into movies. We’ve waited a long time, but change is here.

Where once a few women directors were tolerated, today women directors are celebrated. I think Ava Duvernay is a brilliant director. When I saw the march scene in Selma, I was overwhelmed by what I know it took to direct that scene. Could a man have directed it the same way? Probably, but it’s expected of a man. Who would expect a woman to be able to direct thousands of people? Yet she did.

I think what was empowering about the #MeToo movement, and what connects it to women’s progress in Hollywood is that we learned to support one another, to have one another’s backs and to speak up for another woman when we know she needs it. It isn’t that men have opened the door to us, it’s that we’ve united and, as a group, we’re kicking the door down. We recognize misogyny now—that wasn’t always true. When I saw the women directors moving up the stairs together at Cannes, I wanted to be there too.

This article in Hollywood Reporter includes me: https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/lists/1993-was-oscars-year-woman-has-anything-changed-25-years-1089077/item/year-woman-faye-dunaway-1089058

There is much more I wrote on the subject if interested. They used a small amount.

FTVN: What were your film-making influences growing up and was there a particular film that provided a ‘Eureka!’ moment in your life?

AL: When I first saw a movie, age 3 maybe, I thought the images on the screen were giant people with loud voices. I was not afraid, I was curious. Then I became a little girl who loved Betty Grable. I spent all my nickels trying to get her picture from a vending machine that issued photos of movie stars. Then I became interested in the movie story. I tried to describe images—how stories looked. I wrote little plays.

I acted movies out with my friends on the school playground. I loved Hollywood. Rita Hayworth singing “Put The Blame on Mame, Boys” in Gilda influenced me so that I remember the images to this day. Her song and dance may be the most beautiful movie a ten-year old girl ever fell in love with.

As a young woman I had favorite scenes, rather than favorite movies. The classroom scene in The Last Picture Show where the teacher reads Ode To A Grecian Urn and the camera pans the classroom. You suddenly realize the ancient people on the urn are the young people bored at their desks, not caring about the poem.

The film important to me for the last four years is the Polish film, Ida, directed by Pawlikowski. When I met Mark Cohen, our cinematographer for Any Wednesday, I gave him a DVD of Ida and told him I wanted him to shoot it the same way: long takes, don’t move the camera too much, let the action be the movement inside the frame, let characters move in and out of frame, and let the scenes breathe—give bookends on the takes in case I wanted to continue the shot. He did this and I’m so happy with the look of our film.

When I discovered Bergman movies, the Seventh Seal became my favorite film. I wanted to make images like the characters dancing with death along the mountain top. I began to think I could create those images. That film may have been my Eureka moment.

After the images of Death’s dance, Christians beating themselves, the knight on the beach playing chess with death, it occurred to me that movies are today’s shadows on the walls of Plato’s Cave. We watch in the dark until all life is shut off, the outside doesn’t exist and, eventually, we become the shadows we are watching.