Yves Piat’s acclaimed short NEFTA FOOTBALL CLUB, which is getting buzz on the Festival and Awards circuit, is the uplifting story of two football-mad brothers who discover a donkey on the Algerian / Tunisian border.

Film And TV Now interviewed the director about the film and his hopes for this and other film-making ambitions.

FILM AND TV NOW: Football is such an integral part of this film and a crucial plot point in NEFTA FOOTBALL CLUB. Was the sport always going to be a key part of your story?

YVES PIAT : Indeed, the story is totally related to soccer. From the beginning, we are talking about Riyad Mahrez who is an Algerian football player, about borders and we, end up on boundaries of the football field done with the pushers’ cocaine, big football fans too.

I don’t like the competitive or financial aspects of soccer, but I wanted to highlight the connection between the game and all the stakes around the game, the spontaneous side versus the more cynical side. The two brothers symbolize the gap between childhood and teenage years. Mohammed takes a big risk when he tries to make money with his discovery, but he’s stopped by his little brother’s innocence, who just wants to keep playing.

FTVN: You make a subtle political reference to the rivalry between Algeria and Tunisia when the boy decides to relieve himself in the rocky countryside. Tell us about your background and your own political perspective.

YP: Politics, as practiced by those who govern us nowadays all over the world, is more and more a source of discord when it should be a source of reunification. I wanted to show the innocence of this little boy who is not yet perverted by the concept of fear of the others … The character of Mohammad is free and can go where he wants, even pissing in Algeria, the country of his favorite football player Riyad Mahrez… But his big brother is already acting like an adult who wants to prevent it by referring to the hypothetical danger of crossing the border.

My production team and I tried to make these two young actors come to France to attend the first festival where the movie was shown. We even bought plane tickets and rented a place. But the French authorities refused the visa at the last minute, arguing the children could stay in France illegally after the festival. It’s a bit ironic for the actors who were playing with the idea of the border in the film. To be honest, I’m quite ashamed with the current immigration policy of my own country.

FTVN: Tell us about your locations.

YP: Initially, I wanted to film in Zagora, in the Moroccan desert, and that’s actually where the script began, on the Algerian border. I’m pretty familiar with the region around Zagora since I spent six days walking across the desert with a guide a few years ago, and I went there several times while scouting locations for the film. I knew from the beginning that the desert would have an important role in the film. After I had all my scouting done in southern Morocco and I’d contacted the local authorities, we eventually decided to make the film in Tunisia, barely a month before shooting began and primarily for economic reasons. The Nefta region was ideal because, on one hand, it was still on the Algerian border, as the script had it, and the landscapes were not too far apart (from an hour to an hour and a half at most) and they looked like the ones around Zagora.

I knew what I wanted for the scenery since I’d already done the scouting in Morocco. So we set off with the cinematographer, the focus puller and a fixer to find scenery that I liked in the Redeyef mountains and the entire Tozeur region. We discussed the framing with Valentin Vignet based on what I’d previously drawn out on the storyboard. I like having drawings there from the storyboard cut out because it means you can quickly communicate intentions and ideas.

FTVN : The cinematography provides a very sparse but effective canvas, showing the community and culture at its’ most vivid. Tell us about your Cinematographer and the collaborative process you had with them.

YP: I met Valentin Vignet two years ago while I was looking for a cinematographer. We worked together upstream on the storyboard that I had drawn. I like to work, rework my frame and my staging image in drawing because it allows you to share your ideas visually instantly to the team. Valentine is very effective and very quickly understood all the intentions of the film. He knew how to put himself entirely at the service of the scenario. On the set, he was a light warrior like a Jedi.

FTVN: The two boys who play brothers have wonderful chemistry. Tell us about them as actors and people.

YP: The complicity between the boys was one of the features I was searching for.

First, I cast children from wealthy families. They were used to play in ads, but their acting didn’t fit what I was expecting for this film. I decided to cast children from the poor neighbourhoods of Tunis. I met Eltayef who plays the elder brother the second day of casting… He was very motivated and was always on time, unlike many children from the streets who often sniffed glue before coming to the casting auditions.

I saw hundreds of them and finally chose Eltayef because he was very professional. A great complicity started between us.

On the set, Eltayef was incredibly dedicated to the film, he had a sense of rhythm and he understood very quickly what I asked of him. Every take was good and he was never tired. This child who is now a teenager was really impressive and incredibly kind!

Regarding the little Dali, the other brother, it was a completely different story: I met him a few days before shooting while I was walking in Tunis with Raja Kader, my translator. I wasn’t really satisfied with the young man initially casted for this role. So, as we finally ended up in a dance classroom where there was this boy, Dali, twice as small as the other boys since he was 7 but incredibly free from inhibitions. I was amazed by his presence and asked his father if he wanted his son to appear on a film shooted outside school, in south Tunisia and during holidays. He said yes immediately.

We rehearsed the week before the shooting because both of these children had never made cinema or even been in a theater. In particular, I had to be sure that once there, Dali, the younger one, was not going to give up.

Dali was incredibly pure as an actor but he became tired very quickly on set, but he never gave up. Nevertheless, as a 7 years old child, he was easily distracted by other children, wanted to leave to play with them. One day, he managed to disappear from the set. Five minutes later, he was coming back on a bike he probably fond in the village near the shooting place. He brings the freshness and the innocence that I was looking for this character but it was really difficult to work with such a young actor.

FTVN: How long did it take to shoot and from where did you raise finances and the budget from?

YP: In the beginning, we planned 8 days of shooting but for financial reasons, the production team had to lower the shooting to its minimum which was 6 days of shooting. It was a real challenge to achieve.

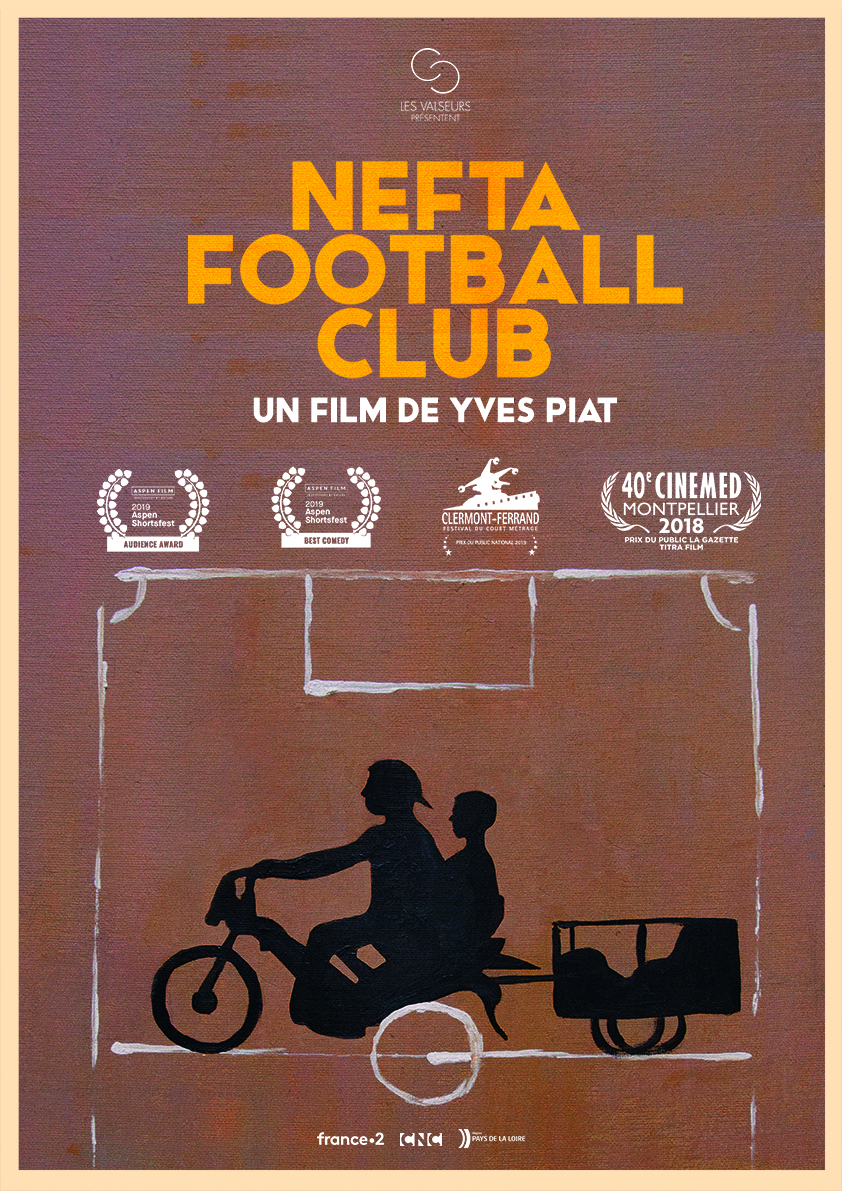

With my producers from Les Valseurs, we applied to a script contest organized by the festival Premiers Plans d’Angers. We won and in consequence, the film was played by France 2 – a french TV channel –. We also got support from the national center of cinema (CNC). Then, the region where I live named Pays de la Loire, helped us for the other half of the budget.

FTVN: You discovered Cinema through your work as a Technician and Studio Manager on a project called Fouillet Wieber. Tell us about your experience and what that project was about, as well as at what point you decided to promote yourself more as a Director.

YP: I actually discovered cinema earlier. At the age of 8, I wanted to become a cartoonist. Then, at the 16, I managed to join a cartoon studio where I was the assistant of Joel Tasset who was kind of head of the artistic department.

After a while, I decided to write stories and making fake ads for fun. Then I joined a film studio called Fouillet Wieber where I worked as an assistant.

Later, I was able to make my first short film financed by the TV channel France 2.

Finally, at 28, I started working on a feature film script with a production company that ended up declaring bankruptcy. It killed five years of work. I stopped making movies for ten years, but never stopped writing.

FTVN: The donkey is also pretty good in the film as well. Tell us where you got the animal from and how old was it at the time of shooting?

YP :Actually, I cast two donkeys … in Nefta. The whole team preferred the other one but I had a strong feeling about the one that was cast … Sometimes love can not be explained (laughs).

FTVN: Bikes also feature in the film. Is this the preferred mode of transport in the region?

YP: I wanted an old blue moped for the aesthetics of the film, a “103 Peugeot blue” as we used in my childhood but it was very difficult to find it in south Tunisia because nowadays, all the motorbikes you can find there are Chinese, without any style. So we had to search the whole city to find the perfect one, powerful enough and easy to handle for a young boy.

FTVN: The film has won some awards on the Festival Circuit. What has your experience been like throughout this?

I am really glad the film has been seen by audiences worldwide, we received so many awards. Thank you to all the jury members all over the world. I was not expecting this success. Some of the awards we received are Oscar-qualifying and it would be a dream come true to be nominated for the Oscars 2020. It’s amazing to see how the audience reacts to the film in festivals. I wished the children of my film could have attended all of this.

FTVN: Finally, where do you see yourself going and what would you like to achieve in the aftermath of NEFTA FOOTBALL CLUB?

YP: I am currently working on a feature film taking place in Jerusalem. An Israeli diplomat suffocates to death while eating sheep, a few days before a peace agreement could be signed. The forensics discover an Israelian bullet in the diplomat’s aorta and the police investigation reveals that the sheep is coming from Palestinian territories. The American emissary in charge of the success of this peace agreement has to handle the situation with extreme caution.