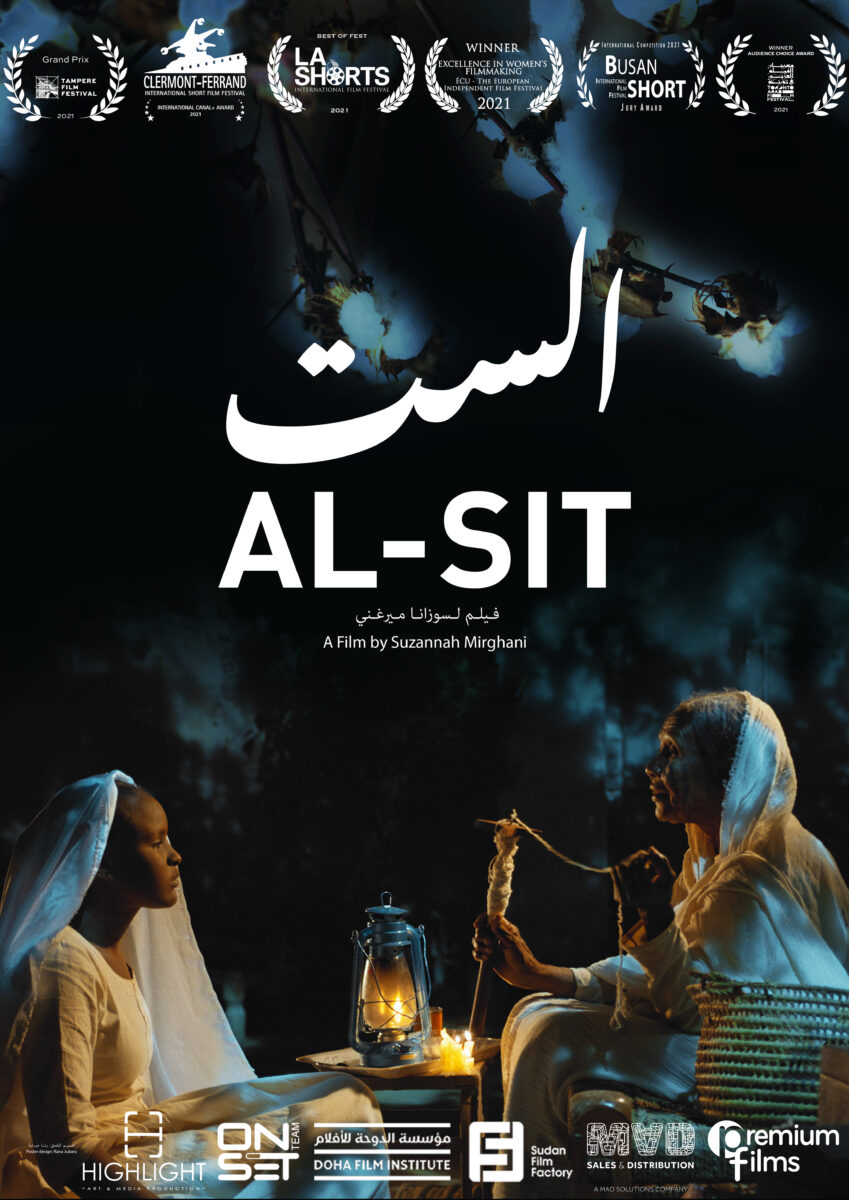

Film-maker Suzannah Mirghani’s Sudanese/Qatari production AL-SIT is the story of a young woman in a Sudanese village attempting to break free of tradition.

Film And TV Now was delighted to speak with the film-maker about her work.

FILM AND TV NOW: Sudan has been seen in a political context in recent years with key events overshadowing its’ evolution as a country. What are your own reflections on the status quo?

SUZANNAH MIRGHANI: Sudan has been through several major political transitions in its lifetime and has had to contend with various forms of political oppression, whether in the form of foreign colonial rule–Ottoman, Egyptian, British–or in the form of a series of domestic national governments.

Each iteration of Sudanese regime has sought to shape the country as an obedient subject, whether under colonial, military, or authoritarian states. As with any repressive form of rule, these governments created the country in their own image and deliberately narrowed the definition of what it means to be Sudanese.

The people of Sudan have had to adapt to each new imaginary over the decades. In 2019, nationwide popular uprisings ousted a 30-year military dictatorship, opening up contemporary space for new definitions of Sudan–in the case of my film, this is a Sudan that is more concerned with the welfare and everyday lived experiences of women and girls.

FTVN: The film deals with the conflict of change over tradition. What was the start-off point for the script?

SM: Conflict over new and traditional ways of life and thinking will always be present, no matter where we are in the world.

In my film, this friction is particularly enhanced because the main characters—the grandmother Al-Sit and the granddaughter Nafisa—are generations apart and so necessarily have different philosophies of life. The film addresses various daily conflicts that all intersect within this one family home: gender relations, filial piety, women’s rights, childhood marriage, arranged marriage, tradition vs modernity, British colonial cotton exploitation, and neoliberal encroachment.

At its very core, the story revolves around the question of agency. This story portrays the struggle of a young girl’s fight to make her own life choices, which is a universal struggle that audiences can relate to, no matter their cultural background.

FTVN: Cotton is a key backdrop to the story. Tell us about the Sudanese cotton industry and what is its’ place in the global manufacture market?

SM: Cotton is a central character in my film. It is the very first image the audience sees, placing Sudanese cotton front and center of the story. Cotton has been intimately woven into the history of Sudanese cultural and economic practice for centuries, and there is evidence of cotton shrouds in the burial chambers of the ancient Sudanese kingdoms.

These were self-sufficient communities that lived along the Nile, growing cotton for clothing, bedding, and animal feed. These small-scale agricultural efforts were decimated in the modern period, when cotton was industrialized on a massive scale by the British colonial project: the Gezira scheme.

For the British, this was an immensely successful and profitable industry. Cotton became a major export and cash crop, feeding the mills of Northern England and fueling Britain’s industrial revolution. Very little of these profits was given to Sudan, and any of the infrastructural projects built by the British, like roads, bridges, and railways, were primarily in service of the industry and colonial interests, with the idea of development only of secondary benefit to Sudan.

In my film, the struggle over the cotton fields in the contemporary period is mirrored in Nafisa’s struggle for freedom and self-definition.

FTVN: Do you feel that arranged marriages are a virtue or an obstacle for women who desire to empower themselves in the world?

SM: I grew up in Sudan, where I witnessed various versions of the story I portray in AL-SIT.

I know many girls who experienced similar situations to the one in which Nafisa finds herself: watching from the side-lines as their families, and especially their grandmothers, arrange their marriages at early ages. Arranged marriages are everyday occurrences in which family members think they’re acting in the interest of the young girl and doing what’s best for her, despite ultimately undermining her agency.

The traditional practice of an arranged marriage is complex and deeply interwoven into Sudanese culture and family structures. In a country where extended families and multiple generations live in the same household, marriage is not necessarily something that happens between two individuals, but rather something that happens between families—or often within the same family when relatives marry each other.

However, even though families arrange marriages for their children out of a sense of duty, love, and protection, the person who matters the most in this situation, the young betrothed, often ends up side lined and oblivious to the discussions. It’s a delicate situation that is simultaneously callous and caring. Through my film, I try to reveal some of these complexities.

FTVN: Tell us about the significance of Al-Sit. Is this common in all Sudanese villages and how far back does this tradition and character go?

SM: The matriarch is a very respected figure in Sudanese society, and is one that stems from the history of ancient Sudan, which were monarchies ruled by both kings and queens.

Even though modern-day Sudan exists within an overarching patriarchal structure, especially in terms of official politics, it is common for Sudanese families to have a matriarch like Al-Sit, who has very real influence and power over family matters.

Even though she might be a frail old woman, the matriarch often controls the fate of the women and girls in the household, especially when it comes to questions of marriage. Because of the matriarch’s deep knowledge about the history and lineage of the extended family, she is also very often the matchmaker, and family members come to her for advice on who is suitable for whom.

FTVN: Tell us about your cast.

SM: Because there is no film industry in Sudan, there is no readily available talent pool from which one can easily draw, and so we held auditions to select potential actors.

The recent successes of Sudanese film-makers like Amjad Abu Alala, Marwa Zein, Suhaib Gasmelbari, and Hajooj Kuka created a lot of interest for our film and many people came to the auditions, which we held at the Sudan Film Factory (SFF) – Sudan’s preeminent film hub founded by Talal Afifi. We were fortunate to have this kind of institutional support, and SFF gave us audition and rehearsal space and became a partner and supporter in making the film.

We worked with many first-time actors, including Mihad Murtada who plays Nafisa and Mohammed Magdi who plays Nadir. I was impressed with their ability to deliver meaningful performances and to so effectively embody their roles, even though they had absolutely no acting experience or background.

The older actors in the film are stage actors, and all celebrated in their own right when it comes to theater, including the formidable Rabeha Mohammed Mahmoud, who plays Al-Sit; Haram Basher and Alsir Mahjoub, who play Nafisa’s parents; and a guest appearance by Abdalla Jacknoon, who plays Babiker’s father.

We began shooting in January 2020, which was just a few months after the political revolution in Sudan, and so we had a great response from everyone involved. This was a time of great hope and belief in the new direction of the country and there was palpable enthusiasm for the revival of Sudanese cinema, which was obliterated under the previous regime.

FTVN: Tell us about your production team.

SM: Even though Sudan does not have a film industry, we worked with many talented crew members who have learned their trade on the production sets of commercials and television shows.

I worked with my producing partner Eiman Mirghani and my Assistant Director Salwa Al Khalifa to form our team, and we were fortunate to work with Sudan’s most talented professionals: cinematographer Khalid Awad and his Highlight Productions crew, lighting director Moez Al Hajjar and his On Set Team crew, Line Producer Abdalla Osman, Production Manager Enan Mohammed, Art Director Sara Awad, Makeup Artist Rayan Ibrahim, and Costume Designer Simba.

Because the community of film-makers is very small in Sudan, once you know one person working in film, you are very quickly introduced to everyone within that circle, and the chances are that you will end up working with them on future projects.

For some unknown reason, we couldn’t find a professional Sudanese sound recordist, so we flew in our only foreign crew member, Bassam Lebbos from Lebanon.

FTVN: Where did you shoot and for how long?

SM: The entire shoot took 9 days, and pre-production took less than a month.

In some paradoxical way, when a country doesn’t have a film industry, things can sometimes work out easily and efficiently because of the heightened passion of everyone working on the project. Since there are very few films made in Sudan, there was a special sense of affiliation that exceeded job descriptions.

We all did what we had to do to get the film made. For example, we didn’t really have to do any location scouting. When we needed a cotton field, our Production Manager Enan Mohamed offered us his family’s field in the village of Azaza, and when we needed to shoot the interior of a Sudanese house, our Costume Designer Mohamed Elmur “Simba” invited us to shoot in his family home in West Giref.

These became more than just shooting locations, and we engaged with the various households, sharing stories and meals during production. The making of this film became a communal project, and we involved these neighborhoods in one way or the other, whether as extras, caterers, or as spectators in support of the daily shoot.

The curiosity of the community brought a lot of energy and created enthusiasm, which positively affected the making of the film.

FTVN: What are your own family’s reaction to your creative endeavours?

SM: My family members, parents, sisters, and husband, have all invested in AL-SIT in one way or another, whether monetarily or in kind. They were always the first to read drafts of the script and to watch rough cuts of the film.

I value their opinions, not just as artists and writers, but because they share the stories portrayed in AL-SIT and have watched the project grow from the beginning.

FTVN: Your background is mixed-race Russian and Sudanese. How does each respective culture impact on your development as a human being and as a creative film-maker?

SM: I celebrate national and cultural hybridity, not only in my personal life but also in my film-making.

My mixed cultural heritage has equipped me with a diversity of perspectives and I enjoy venturing beyond set guidelines. I know that it is impossible to live outside of the concept of borders, but I like to think that my national hybridity has afforded me a certain degree of critical distance and to always be alert to the fiction of the nation and its imagined communities.

Countries are not so much about the formal state as they are about the culture, the people, the songs, the food, the stories, and my memories growing up. Stories of daily life, of family relationships, and of community kinships are the ones I am most interested in telling when it comes to my films, regardless of the larger questions of national belonging.

FTVN: What issues and themes are you keen to explore in your future work?

SM: I made AL-SIT as a proof of concept towards a larger story. I am currently working on my first feature COTTON QUEEN, which takes the world and characters of AL-SIT and develops them beyond the limited time and space of a short film.

In the feature, I explore the issues of neo-liberal exploitation of the cotton fields, the transformation of family relationships, and the innocent poetry of young love in far greater depth and with added cinematic resonance.

FTVN: You are a media and museum studies graduate and are now expressing your art through the context of film. What is it that fascinates you about each discipline?

SM: Everything I study, whether media or museums, is all interrelated. I like to research topics and to produce various artforms from the same reading materials, whether as scholarly articles, poetic vignettes, or films. I see film-making and museum studies as extensions of each other.

Works of art created through film production or curated for museums and are ultimately destined for public exhibition in one form or another, whether on screen or within physical or virtual gallery space.

FTVN: Diversity and gender are big issues in the entertainment world at present. Where do you feel progress has been made, what would you like to see change and how would you like to help other female film-makers develop?

SM: In recent years, there has been a positive move towards public acknowledgement of gender bias in the film industry.

This is largely as a result of the increase in the numbers of women working in the field but also an increase in those who are willing to speak out against all forms of discrimination, whether related specific issues, such as pay, or to issues of representation more generally.

If women working in film face various difficulties in established film industries, then those women working in film in Sudan have to face even greater challenges, including their struggle against the social grain and conservative attitudes towards women’s activities and visibility in public space. Added to this is the lack of an industry to begin with, making film an unsustainable and precarious choice of employment.

However, because there is no formal film industry structure or tradition in Sudan, there is an opportunity to shape it by being more inclusive of women in leadership roles from the outset.

FTVN: How has the global challenge of the last eighteen months affected your development and evolution as a film-maker?

SM: We were fortunate to have completed production of AL-SIT just a few weeks before the onset of the coronavirus pandemic.

When we went into lock-down, the film went into post-production, and I spent those isolated months working closely with my tireless editor Abdelrahim Kattab, colorist Walter Cavatoi, and sound designer Falah Hannoun. Despite the many challenges, the year 2020 was perhaps the most productive year of my life in terms of film-making.

I completed post-production of AL-SIT and designed a film festival strategy, applying to hundreds of film festivals; I developed my feature film script for COTTON QUEEN; and I took the time to create an experimental desktop documentary called VIRTUAL VOICE, under the mentorship of Cambodian filmmaker Rithy Panh and the Doha Film Institute.

FTVN: Finally, what are you most proud of about this short?

SM: I am proud of the fact that AL-SIT was created with the help and support of family, friends, and film institutions in Sudan and in Qatar.

I was fortunate to receive a production grant from the Doha Film Institute, which was the catalyst for getting the film made, but it was not enough to cover all costs. I was so determined to make this film that I ended up investing my personal funds and collecting the rest from my family.

AL-SIT became a truly communal project in which the cast and crew came together for the duration of the shoot and in the process involved neighbors, family members, and friends. AL-SIT has been doing well at international film festivals, and has won several awards, qualifying it for consideration at the 2022 Academy Awards–something I never would have imagined when I first sat down to write the script.

[…] Interview Special: Suzannah Mirghani: ‘AL-SIT’ […]

Comments are closed.