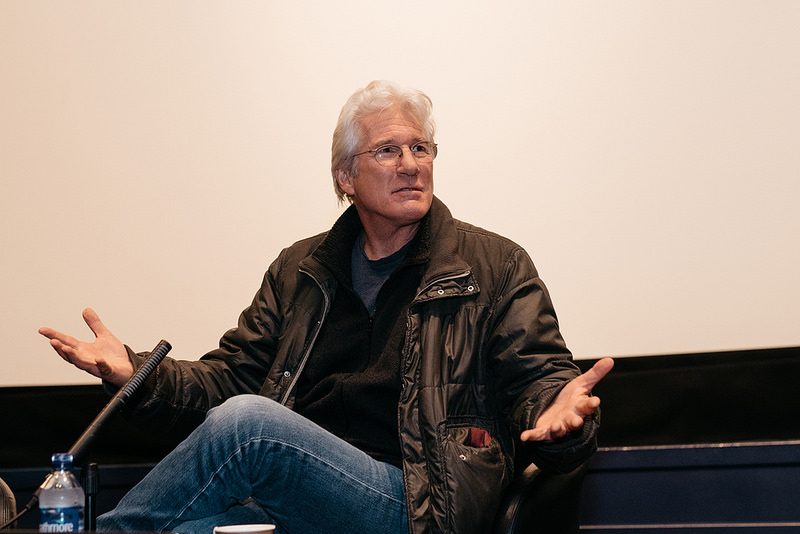

After the screening of TIME OUT OF MIND, RICHARD GERE sat with the Glasgow audience and answered some questions. He was serious and gave detailed answers throughout most of his time there, although there were brilliant flourishes of excitement when it came to responding to the audience with jokes and laughter.

Where did you first get the idea for Time Out of Mind?

Well there was a script…Well, there’s two parallel things that came together; one was I had been working with a group in New York called Coalition for the Homeless. New York, at this point, there are around 60,000 people living on the streets of New York, so it’s omnipresent. A script came to me and I can’t remember what it’s called. What’s it called? Vintage Muscatel was the name of the script. So, I read the script and these was something powerful in it. I decided not to do the script but I kept thinking about the movie and I thought ‘what is it about this film that’s really striking me?’ Obviously, the homeless situation, which I’m tuned to but there was something innate in the script, it hadn’t found itself yet. I couldn’t get it out of my mind, so I ended up buying the script and spent many years, 12 years, developing the script. A lot of it was just taking things away, finding the very simplest line one could possibly find through this guy’s life. An early decision was that there was no back story, I didn’t want to present a back story. I think it’s too easy with a character like this to go ‘oh, well that’s why.’ You don’t see past it because you’ve already made your decision, cause and effect. I wanted to make something that was dealing with the ideal identity very much. How do I define myself? Is there a self? Is the whole idea of a self illusionary? The idea of home, for sure.

There are two levels of home as I see it; one is clearly in this world that we live in, which is we need a home, I need my room, I need my place, and my key that opens up my letterbox with my name on it. You follow that through all the various ways we function in the relative world. There was another home that I wanted to deal with, it was just as important, and that’s the kind of vast interior place that is below the surface of things, or deeper than the surface of things, and much more vast than the surface of things. I wanted to universality of that to empower the more relative reality part of this homeless guy.

You brought director OREN MOVERMAN in, was he the kind of director you immediately thought was appropriate for this type of project and could bring this story to life?

No, it didn’t start that way. Oren and I had known each other from the Todd Haynes movie I’m Not There. Oren is a very well known indie writer and he’s also a wonderful director. His first film was The Messenger, a really first-rate, simple, very realistic film. Anyhow, I had ran into him and I had already kind of figured out how the movie should feel and where the re-writes should be. I started to re-write it myself and realised I was not skilled enough to get it to the degree or the place I wanted to be. So, we ran into each other at a pre-Oscar for new members, he was a new member. We started talking and I told him about this script about a homeless guy and I said ‘ I really need someone like you, Oren, who could get this to the next level’. So, he read it and he also saw in it what I saw, and we just kind of dove in. At that point, frankly, I was going to direct it myself. The more we worked on this and the more immersed I was in the concept of how I wanted to do this, I knew there was no way I was going to be able to direct it.

We had to shoot very quickly, we had the money for about 21 days of shooting, and I really liked Oren’s direction, from what I had seen from the two movies that he had made. He really wanted to direct it himself. So, I said ‘okay, lets run this’. We met with his DP Bobby Bukowski, who is brilliant, and I felt that the three of us really had an infinity of powerful places. Oren took where I was coming from, he took the material I gave him and the entree to shelters in that world and we made this film. This is a reflection of…maybe of my heart from where I’m coming from, but his sense of being a filmmaker – no one else could have made this film but him. He has such a respect for the small things, his disrespect for quick fixes, easy fixes, cheap narrative choices, was very much in his methods for how he makes movies. His use of sound, I never would have thought about that. From the beginning, he said ‘look, we’ve got to get great sound’. The truth was we spent more on sound than we did on anything else in this movie – anything else! It’s quite extraordinary, what we did was we would mix all of these different sounds. I think there was like 50 different languages that we put into this movie. The sounds of the world, the sounds of New York, they almost become the internal sounds in this character – he’s exploding. Oren, I spoke to him yesterday, he’s really sad that he couldn’t be here but we literally just finished another movie two days ago. I went to Ireland yesterday for the Dublin Film Festival, then flew here last night and here I am right now, and I’m leaving right after this to go to London to open the movie there!

Sometimes it’s difficult making films about things people don’t want to hear, and the film portrays this character in a fractured and obscure way. How weary were you of telling the story like this?

When I was trying to figure out what to do with this movie, I knew that the script and the movie kind of had to move into a real realist frame. You know, it had to feel in a way amateurish. It wasn’t professional actors who were in this or professional movie set ups. We had to make choices that erased that expectation that this was like a normal movie. There was a book that started to get some attention in New York called The Land of Lost Souls and it was by a homeless guy, named Cadillac Man. Cadillac Man became a friend of mine, I went to see him and we spent time together, but what was so extraordinary about this book was that he’s not a writer, but he told his story and it was with no sentamentallity, no editorialising. It was very hard line, these are the facts, this is the truth, and I knew this is exactly the way this has to be dealt with. It’s not trying to make emotional responses, it’s not trying to be a normal movie, it’s not trying to be a normal arc of drama. So, that was really the key point to me, and then when Oren and I started speaking, giving him the book, meeting Cadillac Man, taking him to the shelters is when the thing really came to life. I don’t really know if I have answered your question.

I was asking about the risks making a film like this when you want the film to sell.

Well there are several choices there; one is that I had to be honest about it, this is a territory that I knew very well and I couldn’t be dishonest about it. The other choice we made, some of it was imposed on us, was that we had a very small budget. I said this film should not look like it’s a 15 million dollar movie, it should look great, it should have great sound, it shouldn’t look like we shot for six months, it shouldn’t feel like we had all the time in the world, or were in trailers. By the way, my trailer was a rented car, the back seat of a rented car, that’s all I had. You’d have a little space in between shots. Because we had a small budget, the requirement that we fill as many seats as possible was up there. We made it cheaply, we made it exactly the way we wanted to, there were no compromises or any kind of financial interests whatsoever.

Were you tempted to include a ‘Hollywood moment’ in the film?

To be honest with you, I fought for that ending where she leaves because his original script that he gave me… she didn’t leave. I said ‘we can’t do that, man’. I said ‘I don’t want her to go down the street and they hug and kiss and everything’s fine because that’s not real’. Things don’t change that quickly, but you need a space of possibility where they can maybe engage again. Give them a shot, that’s really important and that’s life to me, creating spaces and a possibility where things can get better. Real change takes an enormous amount of time. Whether you’re talking about non-violence or radical self-transformation, real change takes a lot of time and I didn’t want to make this cheaper by making it feel like anything can be fixed in a second.

Some of the other actors like STEVE BUSCEMI, are they friends of yours?

Steve was a friend of Oren’s. I knew Steve before and have enormous respect for him. It was like a community, all of us lived in downtown New York and all of us were kind of committed to the indie world. The last four or five pictures I have made were very small, but his whole life has been doing these very difficult, off the wall movies. Kyra, I don’t even know if you recognised her, she was a homeless woman and that was just an idea so we put that in the script. I just felt that it needed something. The movie is very much about a yearning and a need to connect. That connection seemed to me like it had a purpose as well. That idea came from Cadillac Man’s book, but it was nothing, there was no dialogue, it was just a moment where you saw something happen. Well, Kyra went out, she spent like two or three weeks out with homeless people and she came back with this monologue and I was like ‘that’s it, that’s your part!’

There have been at least three films out recently about homelessness, your film, HECTOR, starring PETER MULLAN, and SHELTER, starring PAUL BETTANY, they have all struggled to get distribution. Do you think that’s because of the views of distributors or that not enough people would see them?

Well, I don’t blame the distributors, they’ve got to make money, they’re in a business. This is not the kind of movie that a distributor is looking for, and I can understand that. What I have told every distributor that we’ve gone into partnership with is that I will work hard on this and I’ll guarantee you that you’ll not lose money on this. You’re not going to make a lot of money, it’s not that kind of movie, it’s a difficult movie. I think it’s true and it’s got honest emotion in it and I think it sticks with you. But, these are hard times for them, and I don’t know if on a Friday night you’re going to say ‘lets go see a homeless movie!’ So, it’s a tough sell. One of the reasons we made it so cheaply is we sell it so cheap to distributors. The upside of this was that we went and gave this away and gave it to local NGOs to use as fundraisers and to raise awareness of homeless communities.

Was that always your intention?

Clearly, you set out to make as good a movie as you can. If you don’t make a good movie, you can’t use it for anything anyway. I felt if we made the film – and I’m really proud of it, I think we made a good film – we would use it that way. So, immediately, we were taking the film to Washington DC and showing it to senators, congressmen, and administration people, people who hadn’t been engaged on this issue, people that had been engaged, and it was a way to generate more energy. We showed it to conventions, homeless organisations in Washington as well. In most of the major cities where we showed the movie we highlighted the local NGOs that were doing this kind of work. It was a moment for them to galvanise more energy.

There are scenes where your character is described as a handsome man. Obviously you are Richard Gere! Was that Oren saying ‘we have to acknowledge this’?

No, I was reading it in a different way because it was all about the past. I really loved the scene with the nurse. That’s as much of the back story as we wanted to give. He was someone who could please women and he didn’t have to work too hard at it. I’m talking about the character here! This is not personal! I liked playing with the fact that, yeah there was a time when… but now no, he says ‘I went from bed to bed, then from couch to couch, now…’ That’s not an option for him now. Basically, he’s saying the same thing to the woman in the shelter when she is taking his information. She says ‘well, you’re a handsome guy’, you can see him just for a moment feel… there’s some kind of glow of appreciation. It goes away quickly but it’s interesting to see characters who have had to deal with their self view changing. I’m not what I used to be. I’m 66 years old now, I’m not a 25 year old stud anymore. Oh, alright I am! Yes I am! I always liked this idea of engaging the past and the present.

Can you see any way of tackling the homeless issue?

It’s not rocket science. It’s really about housing. Now, if you’re going to put someone in permanent housing it’s a beginning point for them to reintegrate themselves. There’s no therapies that are going to work, there’s no social help that’s going to work, there’s no amount of money that’s going to work. It’s the same with all of us; if I feel that scattered and I feel that badly about myself, nothing’s going to work. The beginning point of that reintegration of the personality is having your own place, your place with your key to your letterbox. I say that’s the beginning point. The characteristic of that is the physical reality of a place, but it’s also a community that starts to embrace you and you start to believe in yourself, that I am precious to someone else, I am precious to my family, my tribe, my village, my community. I’m precious, I’m seen, I’m embraced, I’m cared for, I’m cared about – that’s the healing. But, you need housing first and then, with the incredible patience it takes and compassion and skill to bring someone back, most of these NGOs do this incredible work, I’m just blown away by the individuals working at these NGOs and have that kind of patience and don’t burn out and stay at it, year after year after year. I mean, these are saints, they are incredible beings. The community is what saves people and every situation is solved by the community. There’s a thing in New York state, New York City, the right to shelter, if someone shows up and presents themselves as homeless and need a place for the night, by law you have to be given a bed. But, the reality is it’s warehousing, you get that bed and you’re thrown out at seven in the morning. There’s no human touch. It’s a warehousing of a human being. It’s that inability to create a human trust and connection that is very precious, so that’s why it’s never going to work. The shelter system is never going to work.

Some of the scenes looked very nasty and cold, very real.

By the way, we shot in Bellview, this is the first time anyone has shot in Bellview. Those are the actual places and what we shot, the story part that we shot actually a very direct representation of when I took Oren to the shelters and what we saw and experienced. That is exactly the way it is. The paperwork they go through, the craziness around you all the time, the sleeping arrangements, the kind of people you see – that’s the way it is.

I want to talk to you about some of your political work. Because of the size of the market in China, a lot of the Hollywood films are being made to meet that market. Given how you feel about the regime, how does this make you feel?

Well, I made a film maybe 15, 20 years ago called Red Corner and it was actually about businesses going to China, about entertainment businesses going to China. At that point, they were selling junk to the Government. People see movies there on the black market, it’s very strong there. We are seeing China stiffen in ways because it is being so challenged by the realities of how people get information now. This is the worst time in China since Ye Jianying. Intellectuals, writers, human rights lawyers, etc, are being arrested. It’s a really bad time and we don’t know where this is going. There’s some hope that Xi Jinping will be a different type of President, but he’s shown himself to be more controlling than most of his predecessors.

Are you disappointed in the relations between Western nations and the Chinese Government?

We have a mechanism called Most Favoured Nations and what it meant was that there are two tiers of economic relations that we have with the rest of the world. It was Most Favoured Nations, which was like normal relations like what we have with the UK and then it was a tier that didn’t achieve that. It was the only tool we had to express our displeasure with authoritarian dictatorships. Bill Clinton unfortunately removed that so that mechanism is no longer possible. I’m in two minds about this; I think boycotting in one sense is very powerful, boycotting changed South Africa, it had a very powerful effect there. I don’t know if it would have that kind of effect in China. I don’t know if it is necessary for an actual effect because what maybe more important is psychological. Expressing the truth is maybe more important than economic realities. I think that’s the best thing we can do. My own state department, the US State Department, and the administration, by law they have to bring up the Tibet situation in any relations with the Chinese. They have to bring up the human rights situation in China. I don’t know exactly what the situation is with the UK, I know that the last several administrations have not met the Dalai Lama because they didn’t want to harm their relationship with China. Our Presidents do, by law there has to be a relationship. We have something called the Tibet Policy, which I would like to see enacted in the EU as well where there is a fair play by law in terms of human rights – especially Tibet.

[Photographs courtesy of www.NeilThomasDouglas.com]